|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rooms in a Medieval Castle

Rooms in a medieval are largely recognisable by their modern counterparts

in more modest homes. Kitchens are still kitchens. So are pantries

and larders. So are cellars. Bed chambers are now known as bedrooms.

Latrines have become lavatories and bathrooms. Halls have morphed

into entrance halls and dining rooms have taken over one of their

main functions. Solars, Cabinets and Boudoirs have become sitting

rooms, libraries and dressing rooms. Ice houses have been replaced

by refrigerators.

Below are the main rooms found in medieval castles and large manor

houses.

|

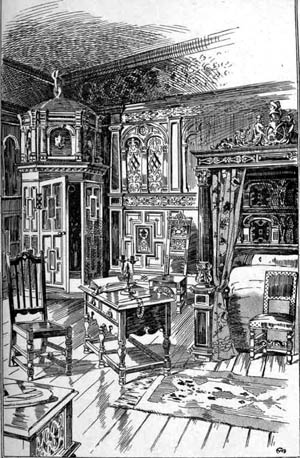

| Bower at Smithills |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

The Great Hall

A great hall is the main room of a royal palace, nobleman's castle

or a large manor house in the Middle Ages, and in the country houses

of the 16th and early 17th centuries. Great halls were found especially

in France, England and Scotland, but similar rooms were also found

in some other European countries.

In the medieval period the room would simply have been referred

to as the "hall" unless the building also had a secondary hall,

but the term "great hall" has been predominant for surviving rooms

of this type for several centuries to distinguish them from the

different type of hall found in post-medieval houses.

A typical great hall was a rectangular room between one and a half

and three times as long as it was wide, and also higher than it

was wide. It was entered through a screens passage at one end, and

had windows on one of the long sides, often including a large bay

window. There was often a minstrel's gallery above the screens passage.

At the other end of the hall was the dais where the top table was

situated. The lord's family's more private rooms lay beyond the

dais end of the hall, and the kitchen, buttery and pantry were on

the opposite side of the screens passage.

Even the royal and noble residences had few living rooms in the

Middle Ages, and a great hall was a multifunction room. It was used

for receiving guests and it was the place where the household would

dine together, including the lord of the house, his gentleman attendants

and at least some of the servants. At night some members of the

household might sleep on the floor of the great hall. From time

to time it might also serve as the lord's courtroom.

The great hall would often have one of the larger fireplaces of

the palace, manor house or castle, frequently large enough to walk

and stand inside it. It was used for warmth and also for some of

the cooking, although for larger structures a medieval kitchen would

customarily lie on a lower level for the bulk of cooking. Commonly

the fireplace would have an elaborate overmantle with stone or wood

carvings or even plasterwork which might contain coats of arms,

heraldic mottoes (usually in Latin), caryatids or other adornment.

In the upper halls of French manor houses, the fireplaces were

usually very large and elaborate. Typically, the great hall had

the most beautiful decorations in it, as well as on the window frame

mouldings on the outer wall. Many French manor houses have very

beautifully decorated external window frames on the large mullioned

windows that light the hall. This decoration clearly marked the

window as belonging to the lord's private hall. It was where guests

slept.

In western France, the early manor houses were centered around

a central ground-floor hall. Later, the hall reserved for the lord

and his high-ranking guests was moved up to the first-floor level.

This was called the salle haute or upper hall (or "high room").

In some of the larger three-storey manor houses, the upper hall

was as high as second storey roof. The smaller ground-floor hall

or salle basse remained but was for receiving guests of any social

order.[1] It is very common to find these two halls superimposed,

one on top of the other, in larger manor houses in Normandy and

Brittany. Access from the ground-floor hall to the upper (great)

hall was normally via an external staircase tower. The upper hall

often contained the lord's bedroom and living quarters off one end.

Occasionally the great hall would have an early listening device

system allowing conversations to be heard in the lord's bedroom

above. In Scotland these devices are called a laird's lug. In many

French manor houses there are small peep-holes from which the lord

could observe what was happening in the hall. This type of hidden

peep-hole is called a judas in French.

Many great halls survive. Two very large surviving royal halls

are Westminster Hall and the Wenceslas Hall in Prague Castle. Penshurst

Place in Kent, England has a little altered 14th century example.

Surviving 16th century and early 17th century specimens in England,

Wales and Scotland are numerous, for example those at Longleat (England),

Burghley House (England), Bodysgallen Hall (Wales), Muchalls Castle

(Scotland) and Crathes Castle (Scotland).

By the late 1700s the great hall was beginning to lose its purpose.

The greater centralisation of power in royal hands meant that men

of good social standing were less inclined to enter the service

of a lord in order to obtain his protection. As the social gap between

master and servant grew, there was less reason for them to dine

together and servants were banished from the hall. In fact, servants

were not usually allowed to use the same staircases as nobles to

access the great hall of larger castles in early times; for example,

the servants' staircases are still extant in places such as Muchalls

Castle. The other living rooms in country houses became more numerous,

specialised and important, and by the late 17th century the halls

of many new houses were simply vestibules, passed through to get

to somewhere else, but not lived in.

Many colleges at Durham, Cambridge, Oxford and St Andrews universities

have halls on the great hall model which are still used as dining

rooms on a daily basis, the largest in such use being that of University

College, Durham. So do the Inns of Court in London and King's College

School in Wimbledon. The "high table" (often on a small dais at

the top of the hall, farthest away from the screens passage) seats

dons (at the universities) and Masters of the Bench (at the Inns

of Court), whilst students (at the universities) and barristers

or students (at the Inns of Court) dine at tables placed at right

angles to the high table and running down the body of the hall,

thus reproducing the hierarchical arrangement of the medieval household.

From the 16th century onwards halls lost most of their traditional

functions to more specialised rooms, both for family members and

guests (e.g. dining parlours, drawing rooms), and for servants (e.g.

servants halls and servants bedrooms in attics or basements) . The

halls of 17, 18th and 19th country houses and palaces usually functioned

almost entirely as vestibules, even if they were architecturally

impressive. There was a revival of the great hall concept in the

late 19th and early 20th centuries, with large halls used for banqueting

and entertaining (but not as eating or sleeping places for servants)

featuring in some houses of this period as part of a broader medieval

revival, for example Thoresby Hall.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bed Chambers

The room in the castle called the Lords and Ladies Chamber, or

the Great Chamber, was intended for use as a bedroom and used

by the lord and lady of the castle - it also afforded some privacy

for the noble family of the castle. This type of chamber was

originally a partitioned room which was added to the end of the

Great Hall. The Lords and Ladies chamber were subsequently situated

on an upper floor when it was called the solar.

The lord and lady's personal attendants were fortunate to stay

with their master or mistress in their separate sleeping quarters.

However, they slept on the floor wrapped in a blanket, but, at least

on the floor, they could absorb some of the warmth of the fireplace.

Even during the warmest months of the year, the castle retained

a cool dampness and all residents spent as much time as possible

enjoying the outdoors. Oftentimes, members wrapped blankets around

themselves to keep warm while at work (from which we derive the

term bedclothes).

The lord, his family and guests had the added comfort of heavy

blankets, feather mattresses, fur covers, and tapestries hanging

on the walls to block the damp and breezes, while residents of lesser

status usually slept in the towers and made due with lighter bedclothes

and the human body for warmth.

|

| |

| Viollet-le-Duc's impression of a XIV to XV Century Castle

Bed chamber |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

The Solar

The room in the castle called the Solar was intended

for sleeping and private quarters and used by the Lord's family.

It became a private sitting room favoured by the family. The solar

suite of rooms was extended to include a wardrobe.

The solar was a room in many English and French medieval manor

houses, great houses and castles. In such houses a need was felt

for more privacy to be enjoyed by the head of the household, and,

especially, by the senior women of the household. The solar was

a room for their particular benefit, in which they could be alone

(or sole) and away from the hustle, bustle, noise and smells of

the Great Hall.

The solar was generally smaller than the Great Hall, because it

was not expected to accommodate so many people, but it was a room

of comfort and status, and usually included a fireplace and often

decorative woodwork or tapestries/wall hangings.

In manor houses of western France, the solar was sometimes a separate

tower or pavilion, away from the ground-floor hall and upper hall

(great hall) to provide more privacy to the feudal lord and his

family.

The etymology of solar is often mistaken for having to do with

the sun but this is not so. This error may result from the common

usage of the solar; embroidery, reading, writing, and other generally

solitary activities. These activities would need good sunlight,

and it is true that most solars were built facing south to take

maximum advantage of daylight hours, but that characteristic was

neither required nor the source of the name. The name fell out of

use after the sixteenth century and its later equivalent was the

drawing room.

|

| Solar at Kentwell |

|

| |

| Solar at Smithills, Bolton |

|

|

|

|

|

Bathrooms, Lavatories and Garderobes

Bathrooms,

so common in the classical world disappeared in Medieval Europe

- except in monasteries. Except in certain circumstances baths were

not required for ordinary people - until Victorian times cleanliness

was fundamentally ungodly. Bathrooms,

so common in the classical world disappeared in Medieval Europe

- except in monasteries. Except in certain circumstances baths were

not required for ordinary people - until Victorian times cleanliness

was fundamentally ungodly.

Baths were taken in transportable wooden tubs, In summer the sun

could warm the water and the bather. The tub could be moved inside

when the weather worsened.

Privacy was ensured with a tent or canopy.

In English a garderobe has come to mean a primitive toilet in a

castle or other medieval building, usually a simple hole discharging

to the outside. Such toilets were often placed inside a small chamber,

leading by association to the use of the term garderobe to describe

them.

Technically garderobes were small rooms or large cupboards (closets)

in which the latrine was located. These closets were often used

for storing valuables

A description of the garderobe at Donegal castle indicates that

during the time when the castle garderobe was in use it was believed

that ammonia was a disinfectant and that visitor's coats and cloaks

were kept in the garderobe.

Depending on the structure of the building, garderobes could lead

to cess pits or moats. Many can still be seen in Norman and Medieval

castles and fortifications. They became obsolete with the introduction

of indoor plumbing.

Given the likely updrafts in a medieval castle, a chamber pot generally

remained close to the bedside.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kitchens, Pantries, Larders and Butteries

In most households, including early castles, cooking was done on

an open hearth in the middle of the main living area, to make efficient

use of the heat. This was the most common arrangement for most of

the Middle Ages, so the kitchen was combined with the dining hall.

Towards the Late Middle Ages a separate kitchen area began to evolve.

The first step was to move the fireplaces towards the walls of the

main hall, and later to build a separate building or wing that contained

a dedicated kitchen area, often separated from the main building

by a covered arcade. This way, the smoke, odours and bustle of the

kitchen could be kept out of sight of guests, and the fire risk

to the main building reduced.

Many basic variations of cooking utensils available today, such

as frying pans, pots, kettles, and waffle irons, already existed

in great households. Other tools more specific to cooking over an

open fire were spits of various sizes, and material for skewering

anything from delicate quails to whole oxen. There were also cranes

with adjustable hooks so that pots and cauldrons could easily be

swung away from the fire to keep them from burning or boiling over.

Utensils were often held directly over the fire or placed into embers

on tripods.

There were also assorted knives, stirring spoons, ladles and graters.

In wealthy households one of the most common tools was the mortar

and sieve cloth, since many medieval recipes called for food to

be finely chopped, mashed, strained and seasoned either before or

after cooking. This was based on a belief among physicians that

the finer the consistency of food, the more effectively the body

would absorb the nourishment. It also gave skilled cooks the opportunity

to elaborately shape the results. Fine-textured food was also associated

with wealth; for example, finely milled flour was expensive, while

the bread of commoners was typically brown and coarse. A typical

procedure was farcing (from the Latin farcio, "to cram"), to skin

and dress an animal, grind up the meat and mix it with spices and

other ingredients and then return it into its own skin, or mold

it into the shape of a completely different animal.

The kitchen staff of huge noble or royal courts occasionally numbered

in the hundreds, including: pantlers, bakers, waferers, sauciers,

larderers, butchers, carvers, page boys, milkmaids, butlers and

scullions. Major kitchens of households had to cope with the logistics

of daily providing at least two meals for several hundred people.

Guidelines on how to prepare for a two-day banquet include a recommendation

that the chief cook should have at hand at least 1,000 cartloads

of "good, dry firewood" and a large barnful of coal.

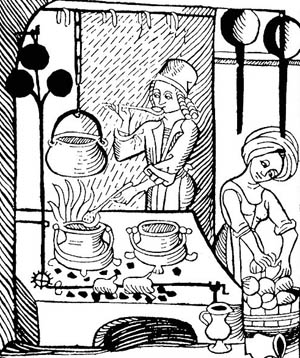

|

| A cook at the stove with a cook's trademark ladle; woodcut

illustration from Kuchenmaistrey, the first printed cookbook

in German, woodcut, 1485. |

|

| |

| |

| Kitchen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pantry

A pantry is a room where food, provisions or dishes are stored

and served in an ancillary capacity to the kitchen. The derivation

of the word is from the same source as the Old French term paneterie;

that is from pain, the French form of the Latin pan for

bread.

In a late medieval hall, there were separate rooms for the various

service functions and food storage. A pantry was where bread was

kept and food preparation associated with it done. The head of the

office responsible for this room was referred to as a pantler. .

|

|

|

|

Larder

A larder is a cool area for storing food prior to use. Larders

were commonplace in houses before the widespread use of the refrigerator.

Essential qualities of a larder are that it should be:as cool as

possible, close to food preparation areas, constructed so as to

exclude flies and vermin, easy to keep clean, and equipped with

shelves and cupboards appropriate to the food being stored.

In the northern hemisphere, most houses would arrange to have their

larder and kitchen on the north or east side of the house where

it received least sun.

Many larders have small unglazed windows with the window opening

covered in fine mesh. This allows free circulation of air without

allowing flies to enter. Many larders have tiled or painted walls

to simplify cleaning. Older larders and especially those in larger

houses have hooks in the ceiling to hang joints of meat or game.

Others have insulated containers for ice.

A pantry may contain a a stone slab or shelf used to keep food

cool in the days before refrigeration was domestically available.

In the late medieval hall, a thrawl would have been appropriate

to a larder. In a large or moderately large nineteenth century house,

all these rooms would have been placed as low in the building as

possible, or as convenient, in order to use the mass of the ground

to retain a low summer temperature. For this reason, a buttery was

usually called the cellar by this stage.

In medieval households the larderer was an officer responsible

for meat and fish, as well as the room where these commodities were

kept. . The Scots term for larder was the spence, and so in Scotland

larderers (also pantlers and cellarers) were known as spencers.

This is one of the derivations of the modern surname.

The office only existed as a separate office in larger households.

It was closely connected with other offices of the kitchen, such

as the saucery and the scullery.

|

| Larder |

|

| |

| Larder |

|

|

|

|

Buttery

A buttery was a domestic room in a castle or large medieval house.

It was one of the offices pertaining to the kitchen. It was generally

a room close to the Great Hall and was traditionally the place from

which the yeoman of the buttery served beer and candles to those

lower members of the household not entitled to drink wine.

The room takes its name from the beer butts (barrels) stored there.

The buttery generally had a staircase to the beer cellar below.

The wine cellars, however, belonged to a different department, that

of the yeoman of the cellar and in keeping with the higher value

of their contents were often more richly decorated to reflect the

higher status of their contents.

From the mid-17th century, as it became the custom for servants

and their offices to be less conspicuous and sited far from the

principal reception rooms, the Great Hall and its neighbouring buttery

and pantry lost their original uses. While the Great Hall often

became a grand staircase hall or large reception hall, the smaller

buttery and pantry were often amalgamated to form a further reception

or dining room.

|

| Buttery (Barleyhall, York) |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Gatehouses and Guardrooms

A gatehouse is a fortified structure built over the gateway to

a city or castle. The modern gatehouse is a feature of European

castles, manor houses and mansions.

Gatehouses made their first appearance in the early antiquity when

it became necessary to protect the main entrance to a castle or

town. Over time, they evolved into very complicated structures with

many lines of defence.

Strongly fortified gatehouses would normally include a drawbridge,

one or more portcullises, machicolations, arrow loops and possibly

even murder-holes where stones would be dropped on attackers. In

the late Middle Ages, some of these arrow loops might have been

converted into gun loops (or gun ports).

Sometimes gatehouses formed part of town fortifications, perhaps

defending the passage of a bridge across a river or a moat, as Monnow

Bridge in Monmouth. York has four important gatehouses, known as

"Bars", in its city walls.

The French term for gatehouse is logis-porche. This could be a

large, complex structure that served both as a gateway and lodging

or it could have been composed of a gateway through an enclosing

wall. A very large gatehouse might be called a châtelet (small

castle).

At the end of the Middle Ages, gatehouses in England and France

were often converted into beautiful, grand entrance structures to

manor houses or estates. Many of them became a separate feature

free-standing or attached to the manor or mansion only by an enclosing

wall. By this time the gatehouse had lost its defensive purpose

and had become more of a monumental structure designed to harmonise

with the manor or mansion.

|

| Gatehouse at Stirling Castle in Scotland |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

Chapels & Oratories

Throughout the medieval period Christianity of the form currently

in power was obligatory, with the interment exception of Jews. Almost

everyone was obliged to profess Christian belief and to act accordingly.

Only the most powerful nobles (like Frederick II) were able to express

disbelief without risking their lives.

The room in the castle called the Chapel was intended for prayer

and used by all members of the castle household. It was usually

close to the Great hall. It was often built two stories high, with

the nave divided horizontally. The Lord's family and dignitaries

sat in the upper part and the servants occupied the lower part of

the chapel

An Oratory was intended for use as a private chapel. It was a

room attached to the chapel that could be used for private prayer

by the Lord's family.

Today, the owners of Many Castles and Manor Houses will (for a

fee) allow people to get married in their Castle chapels with the

reception then taking place in the Castle.

Click

here for a list of Castles offering Weddings and Civil Partnerships

|

| The Chapel at Windsor Castle |

|

|

|

|

Cabinets and Boudoirs

Heating the main rooms in large palaces or mansions in the winter

was difficult, and small rooms were more comfortable. They also

offered more privacy from servants, other household members, and

visitors. Typically such a room would be for the use of a single

individual, so that a house might have two or more. Names varied:

cabinet, closet, study (from the Italian studiolo), or office.

A cabinet was one of a number of terms for a private room in the

castles and palaces of Early Modern Europe, serving as a study or

retreat, usually for a man. A cabinet would typically be furnished

with books and works of art, and sited adjacent to his bedchamber

(evolving into the equivalent of the Italian Renaissance studiolo

and the modern English studio). Such a room might be used as a study

or office, or just a sitting room.

In the Late Medieval period, such requirements for privacy had

been served by the solar of the English gentry house.

Cabinets could be used for small private meetings - for example

between the king and his ministers. Since the reign of King George

I, the Cabinet – which takes its name from the room – has been

the principal executive group of British government, and the term

has been adopted in most English-speaking countries. Phrases such

as "cabinet counsel", meaning advice given in private to the monarch,

occur from the late 16th century.

The word c cabinet in English was often used for strongrooms, or

treasure-stores - the tiny but exquisite Elizabethan tower strongroom

at Lacock Abbey might have been so called - but also in the wider

sense.

In Elizabethan England, such a private retreat would most likely

be termed a closet, the most recent in a series of developments

in which people of means found ways to withdraw from the public

life of the household as it was lived in the late medieval great

hall. This sense of "closet" has continued use in the term "closet

drama", which is a literary work in the form of theatre, intended

not to be mounted nor publicly presented, but to be read and visualised

in privacy. Two people in intimate private conversation are said

to be "closetted".

Much later closets were ideal locations for lavatories - which

thus became known as water closets or WCs.

There is a rare surviving cabinet or closet with its contents probably

little changed since the early 18th century at Ham House in Richmond,

London. It is less than ten feet square, and leads off from the

Long Gallery, which is well over a hundred feet long by about twenty

wide, giving a rather startling change in scale and atmosphere.

As is often the case (at Chatsworth House for example), it has an

excellent view of the front entrance to the house, so that comings

and goings can be discreetly observed. Most surviving large houses

or palaces, especially from before 1700, have such rooms, but (again

as at Chatsworth) they are very often not displayed to visitors.

Boudoirs

A boudoir is a lady's private bedroom, sitting room or dressing

room. The term derives from the French verb bouder, meaning "to

pout" - because the room was seen as a "pouting room".

Historically, the boudoir formed part of the private suite of rooms

of a lady, for bathing and dressing, adjacent to her bedchamber.

In this it was the female equivalent of the male cabinet.

In later periods, the boudoir was used as a private drawing room,

and was used for other activities, such as embroidery or entertaining

intimate acquaintances.

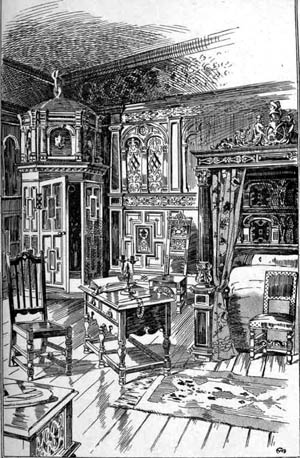

|

| Panelled Cabinet |

|

| |

| Cabinet room at 10 Downing Street |

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Storerooms, Undercrofts & Cellars

Casemate

A casemate was originally a vaulted chamber usually constructed

underneath the rampart. It was intended to be impenetrable and could

be used for sheltering troops or stores.

Place of Arms

The room in the castle called the Place of Arms was a large area

in a covered way, where troops could assemble.

Undercroft

An undercroft is traditionally a cellar or storage room, often

vaulted.

While some were used as simple storerooms, others were rented out

as shops. For example, the undercroft rooms at Myres Castle in Scotland

circa 1300 were used as the medieval kitchen and a range of stores.

The undercroft beneath the House of Lords in the Palace of Westminster

in London was rented out to the conspirators behind the Gunpowder

Plot in 1605.

Many early medieval undercrofts were vaulted or groined, such as

the vaulted chamber at Beverston Castle or the groined stores at

Myres Castle.

Undercrofts were commonly built in England and Scotland throughout

the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries.

Buildings with historic examples

England

- Banqueting House, Palace of Whitehall, London

- Blakeney Guildhall, Blakeney, Norfolk

- Bradenstoke Abbey, Wiltshire

- Coventry Cathedral, Coventry, West Midlands

- Canterbury Cathedral, Canterbury, Kent

- Carlisle Cathedral, Carlisle, Cumbria

- Dragon Hall, Norwich, Norfolk

- Durham Castle, Undercroft, Durham

- Eastbridge Hospital, Canterbury, Kent

- Forde Abbey, Dorset.

- Fountains Abbey, North Yorkshire

- Jurnet's House, Norwich, Norfolk

- Moyse's Hall Museum, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk

- Norton Priory, Runcorn, Cheshire

- Rufford Abbey, Nottinghamshire

- St Nicholas Priory, Exeter, Devon

- St Pancras Station, London

- Warwick Castle, Warwickshire

- Westminster Abbey, London

- Windsor Castle

- Wingfield Manor, Derbyshire

- York Minster, York, North Yorkshire

Other examples

- Dublin Castle, Dublin, Ireland

- Dundrennan Abbey, Dundrennan, Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland

- Cardiff Castle, Cardiff, Wales

- Castell Coch, Cardiff, Wales

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ice Houses

An ice-house was just that: a special insulated house to keep ice.

During the winter, ice and snow would be taken into the ice house

and packed with insulation, often straw or sawdust. It would remain

frozen for many months, often until the following winter, and could

be used as a source of ice during summer months. The main application

of the ice was the storage of perishable foods, but it could also

be used simply to cool drinks, or allow ice-cream and sorbet desserts

to be prepared.

Ice houses are found in ha-ha walls, house and stable basements,

woodland banks, and even open fields.

The most common designs involved underground chambers, usually

man-made, and built close to natural sources of winter ice such

as freshwater lakes. Ice houses varied in design depending on the

date and builder, but were mainly conical or rounded at the bottom

to hold melted ice. They usually had a drain to take away any water.

In some cases ponds were built nearby specifically to provide the

ice in winter.

The ice house was formally introduced to Britain around 1660, although

there are occasional examples surviving from the medieval period.

British ice houses were commonly brick lined, domed structures,

with most of their volume underground. The idea for formal ice houses

was brought to Britain by travellers who had seen similar arrangements

in Italy, where peasants collected ice from the mountains and used

it to keep food fresh inside caves.

Usually

only castles and large manor houses had purpose-built buildings

to store ice. Many examples of ice houses exist in the UK some of

which have fallen into a poor state of repair. Good examples of

19th-century ice houses can be found at Ashton Court, Bristol, Grendon,

Warwickshire, and at Christchurch Mansion, Ipswich, Suffolk, Moggerhanger

Park, Bedfordshire Petworth House, Sussex, Danny House, Sussex,

Ayscoughfee Hall, Spalding, Rufford Abbey, and Eglinton Country

Park in Scotland and Parlington Hall in Yorkshire. Game larders

and venison larders were sometimes marked on ordnance survey maps

as ice houses. Usually

only castles and large manor houses had purpose-built buildings

to store ice. Many examples of ice houses exist in the UK some of

which have fallen into a poor state of repair. Good examples of

19th-century ice houses can be found at Ashton Court, Bristol, Grendon,

Warwickshire, and at Christchurch Mansion, Ipswich, Suffolk, Moggerhanger

Park, Bedfordshire Petworth House, Sussex, Danny House, Sussex,

Ayscoughfee Hall, Spalding, Rufford Abbey, and Eglinton Country

Park in Scotland and Parlington Hall in Yorkshire. Game larders

and venison larders were sometimes marked on ordnance survey maps

as ice houses.

The idea was old even in Medieval times. Ice houses originally

invented in Persia were buildings used to store ice throughout the

year. An inscription from 1700 BC in northwest Iran records the

construction of an icehouse, "which never before had any king built."

In China, archaeologists have found remains of ice pits from the

seventh century BC, and references suggest they were in use before

1100 BC. Alexander the Great around 300 BC stored snow in pits dug

for that purpose. In Rome in the third century AD, snow was imported

from the mountains, stored in straw-covered pits, and sold from

snow shops.

|

| The entrance to a medieval ice house at St. Germain's House

near Edinbugh |

|

| |

| The icehouse at Coome Park undergoing restoration |

|

| |

| Rufford

Abbey Ice House 1 |

|

| |

|

|

|

Dovecotes

A dovecote is a building intended to house pigeons or doves.

Dovecotes may be square or circular free-standing structures or

built into the end of a house or barn. They generally contain pigeonholes

for the birds to nest. Pigeons and doves were an important food

source historically in Western Europe and were kept for their eggs,

flesh, and dung.

In Medieval Europe, the possession of a dovecote was a symbol of

status and power and was regulated by law. Only nobles had this

special privilege known as droit de colombier.

Their location is chosen away from large trees that can house raptors

and shielded from prevailing winds and their construction obeys

a few safety rules: tight access doors and smooth walls with a protruding

band of stones (or other smooth surface) to prohibit the entry of

climbing predators such as rats, martens, and weasels. The exterior

facade was, if necessary, only evenly coated by a horizontal band,

in order to prevent their ascent.

Dovecote materials can be very varied and shape and dimension extremely

diverse:

- the square dovecote with quadruple vaulting: built before the

fifteenth century ( Roquetaillade Castle, Bordeaux) or Saint-Trojan

near Cognac)

- the cylindrical tower: fourteenth century to the sixteenth century,

it is covered with curved tiles, flat tiles, stone lauzes roofing

and occasionally with a dome of bricks. A window or skylight is

the only opening.

- the dovecote on stone or wooden pillars, cylindrical, hexagonal

or square;

- the hexagonal dovecote (like the dovecotes of the Royal Mail

at Sauzé-Vaussais);

- the square dovecote with flat roof tiles in the seventeenth

century and a slate roof in the eighteenth century;

- the lean-to structure against the sides of buildings.

- Inside a dovecote could be virtually empty (boulins being located

in the walls from bottom to top), the interior reduced to only

the structure of a rotating ladder, or "potence", allowing the

collection of eggs or squabs and maintenance.

The oldest known dovecotes are the fortified dovecotes of Upper

Egypt, and the domed dovecotes of Iran. In the dry regions, the

droppings were in great demand and were collected on uniformly cleaned

braids.

Dovecotes were built by the Romans, who knew them as Columbaria.

They seem to have introduced them to Gaul. The presence of dovecotes

is not noted in France before the Roman invasion of Gaul by Caesar.

The pigeon farm was then a passion in Rome: the Roman columbarium

, generally round, had its interior covered with a white coating

of marble powder. Varro, Columella and Pliny the Elder wrote works

on pigeon farms and dovecote construction.

Dovecotes of France

The French word for dovecote is pigeonnier or colombier. In some

French provinces, especially Normandy, dovecotes were built of wood

in a very stylised way. Stone was the other popular building material

for these old dovecotes. These stone structures were usually built

in circular, square and occasionally octagonal form. Some of the

medieval French abbeys had very large stone dovecotes on their grounds.

In Brittany the dovecote was sometimes built directly into the

upper walls of the farmhouse or manor-house. In rare cases, it was

built into the upper gallery of the lookout tower (for example at

the Toul-an-Gollet manor in Plesidy, Brittany). Dovecotes of this

type are called tour-fuie in French.

Some

of the larger châteaux-forts such as the Château de

Suscinio in Morbihan, still have a complete dovecote standing on

the grounds, outside the moat and walls of the castle. Some

of the larger châteaux-forts such as the Château de

Suscinio in Morbihan, still have a complete dovecote standing on

the grounds, outside the moat and walls of the castle.

The dovecote interior, the space granted to the pigeons, is divided

into a number of boulins (pigeon holes). Each boulin is the lodging

of a pair of pigeons. These boulins can be in rock, brick or cob

(adobe) and installed at the time of the construction of the dovecote

or be in pottery (jars lying sideways, flat tiles, etc.), in braided

wicker in the form of a basket or of a nest. It is the number of

boulins that indicates the capacity of the dovecote. The one at

the Château d'Aulnay with its 2,000 boulins and the one at

Port-d'Envaux with its 2,400 boulins of baked earth are among the

largest ones in France.

In the Middle Ages, particularly in France, the possession of a

colombier à pied (dovecote on the ground accessible by foot), constructed

separately from the corps de logis of the manor-house (having boulins

from the top down), was a privilege of the seigneurial lord. He

was granted permission by his overlord to build a dovecote or two

on his estate lands. For the other constructions, the dovecote rights

(droit de colombier) varied according to the provinces. They had

to be in proportion to the importance of the property, placed in

a floor above a henhouse, a kennel, a bread oven, even a wine cellar.

Generally the aviaries were integrated into a stable, a barn or

a shed, and were permitted to use no more than 2.5 hectares of arable

land.

Although they produced an excellent fertiliser (known as colombine),

the lord's pigeons were often seen as a nuisance by the nearby peasant

farmers, in particular at the time of sowing of new crops. In numerous

regions where the right to possess a dovecote was reserved solely

for the nobility , the complaint rolls very frequently recorded

formal requests for the suppression of this privilege and a law

for its abolition, which was finally ratified on 4 August 1789 in

France.

Many ancient manors in France have a dovecote (still standing or

in ruins) in one section of the manorial enclosure or in nearby

fields.

The Romans may have introduced dovecotes or columbaria to Britain

since pigeon holes have been found in Roman ruins at Caerwent. However

it is believed that doves were not commonly kept there until after

the Norman invasion. The earliest known examples of dove-keeping

occur in Norman castles of the 12th century (for example, at Rochester

Castle, Kent, where nest-holes can be seen in the keep), and documentary

references also begin in the 12th century. The earliest surviving,

definitely-dated free-standing dovecote in this country was built

in 1326 at Garway in Herefordshire.

Many ancient manors in the United Kingdom have a dovecote (still

standing or in ruins) in one section of the manorial enclosure or

in nearby fields.

Early purpose-built dovecotes in Scotland are of a "beehive" shape,

circular in plan and tapering up to a domed roof with a circular

opening at the top. In the late 16th century they were superseded

by the "lectern" type, rectangular with a monopitch roof sloping

fairly steeply in a suitable direction. In Scotland a dovecote is

known as a Doocot.

Phantassie Doocot is an unusual example of the beehive type topped

with a monopitch roof, and Finavon Doocot of the lectern type is

the largest doocot in Scotland, with 2,400 nesting boxes. Doocots

were built well into the 18th century in increasingly decorative

forms, then the need for them died out though some continued to

be incorporated into farm buildings as ornamental features. The

20th century saw a revival of doocot construction by pigeon fanciers,

and dramatic towers clad in black or green painted corrugated iron

can still be found on wasteland near housing estates in Glasgow

and Edinburgh.

|

| Colombier at Manoir d'Ango near Dieppe |

|

| |

| Schematic showing the interior of a dovecote |

|

| |

| Interior of Dovecote at Penmon Priory |

|

| |

| Dovecote at Nymans Gardens, West Sussex, England |

|

| |

| Ross Doocot |

|

|

|

|

Apartments

Apartments are not modern inventions. Great castles were often

divided into apartments, each apartment belonging to an important

resident - for example the Lord's widowed mother, his brothers and

sisters, and visiting dignitaries.

This model, once common in all great houses, survives among British

royalty. Most royal palaces are divided into apartments, each belonging

to a senior member of the Royal Family.

|

| Kensington Palace - the official residence of The Duke and

Duchess of Gloucester; the Duke and Duchess of Kent; and Prince

and Princess Michael of Kent. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

More on Life in a Medieval Castle

Introduction

to Life in a Medieval Castle

Rooms

in a Medieval Castle

Officers

& Servants in a Medieval Castle

Medieval

Clothing

Medieval

Food & Cooking

Medieval

Drinks

Medieval

Gardens

Medieval

Warfare:

Medieval

Taxes

Medieval

Games & Pastimes

The

Feudal System

Commendation

Desmenes

Rivers

& Fishponds

Mills:

Windmills

and Water

Mills

|

|

The Great Hall at Christ Church College,

Oxford

|

|

| |

|

Falconer

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

A baker with his assistant. As seen in the

illustration, round loaves were among the most common.

|

|

| |

| |

| |

место преступления

.

| |

Once you enter that single door into the keep you come into a room called the disarming room. This is where all visitors would give up their weapons. We can't have people walking around with weapons inside the keep. You just never know who to trust.

Once you enter that single door into the keep you come into a room called the disarming room. This is where all visitors would give up their weapons. We can't have people walking around with weapons inside the keep. You just never know who to trust.  And this is that massive main door too the keep. It is very thick and solid. This actual door and lock are about 250 years old. The key to this door is about a foot in size. Pretty solid stuff. We are standing right inside the disarming room.

And this is that massive main door too the keep. It is very thick and solid. This actual door and lock are about 250 years old. The key to this door is about a foot in size. Pretty solid stuff. We are standing right inside the disarming room. There are various rooms in the keep and they look like this. The wooden floor is the same as it would have been hundreds of years ago.

There are various rooms in the keep and they look like this. The wooden floor is the same as it would have been hundreds of years ago.  Another fascinating defense measure inside the keep was the way the stairwells were made. They would have a clockwise rotation so defenders of the keep could easily use their right hand sword hand. Attackers trying to go up the stairs would have their sword hand agains the inner wall. That made it difficult for them to swing their swords.

Another fascinating defense measure inside the keep was the way the stairwells were made. They would have a clockwise rotation so defenders of the keep could easily use their right hand sword hand. Attackers trying to go up the stairs would have their sword hand agains the inner wall. That made it difficult for them to swing their swords. Now, this is a little difficult to see but in that alcove on the left there is a hole in the bottom. That is the toilet chute! Yup, they had to take care of business in the keep. And that chute goes all the way down to a room in the bottom.

Now, this is a little difficult to see but in that alcove on the left there is a hole in the bottom. That is the toilet chute! Yup, they had to take care of business in the keep. And that chute goes all the way down to a room in the bottom.  Here is a fireplace inside the castle main room. And the big thing about this is that it was added centuries after the keep was first built! Yup, it was a marvel of an upgrade and renovation! Until then this keep was very cold.

Here is a fireplace inside the castle main room. And the big thing about this is that it was added centuries after the keep was first built! Yup, it was a marvel of an upgrade and renovation! Until then this keep was very cold.  And here is a look up through the fireplace air chute. It is called a fumarelli and it curves and twists on its way up to bring the smoke out. But the curving and twisting was to prohibit rain from coming straight down and into the keep , putting out the fire.

And here is a look up through the fireplace air chute. It is called a fumarelli and it curves and twists on its way up to bring the smoke out. But the curving and twisting was to prohibit rain from coming straight down and into the keep , putting out the fire.