Русалки, сирены и Мария, королева Шотландии: иконы распутства и гордости

Часть

Королевство и власть

серия книг (QAP) Аннотация

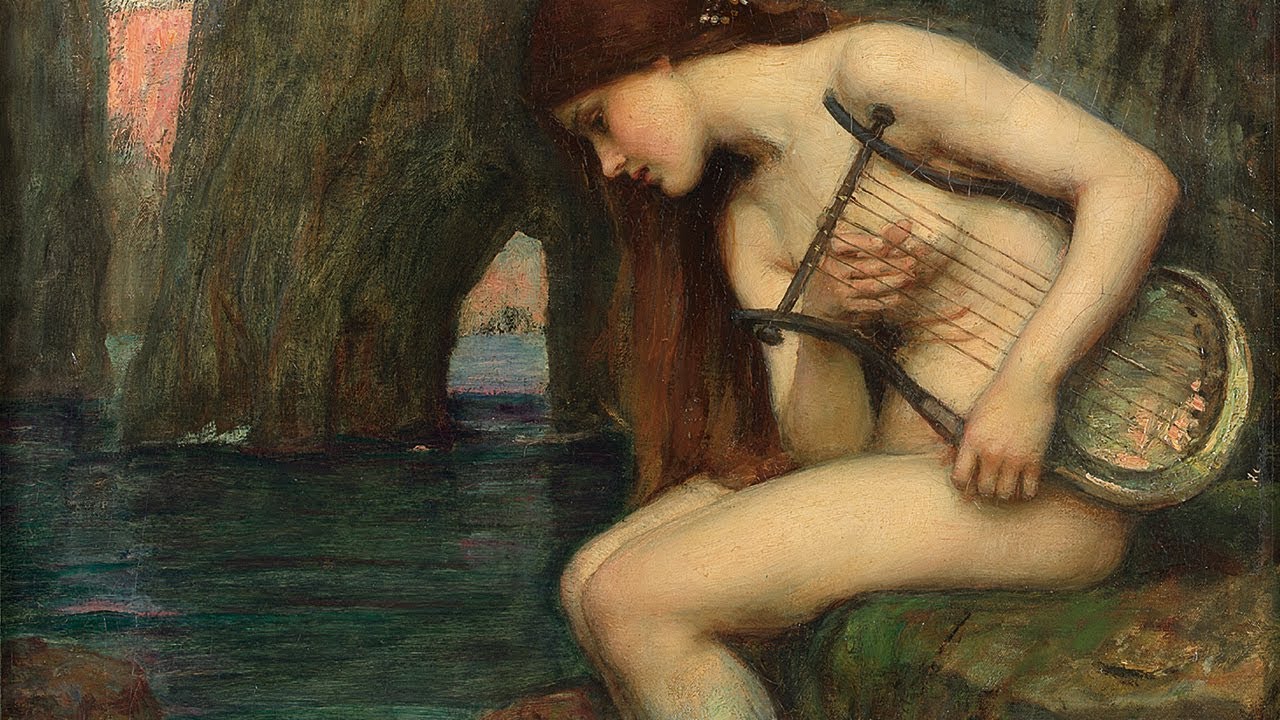

Многочисленные намёки на сирен (которые считаются взаимозаменяемыми с русалками) и их расслабляющее действие на ничего не подозревающих мужчин, которые встречались на их пути, встречаются во многих символических и литературных произведениях раннего современного периода. 1 < / sup> Их песни сначала соблазняют неосторожных жертв чарующим звуком, прежде чем бросить их на камни разрушения. В Комедии ошибок Уильяма Шекспира (около 1592 г.), например, Антифол Сиракузский, поклявшись, что Адриана не его жена, умоляет Люциану, «милую русалку», с которой он стал страстным увлечением: «Пой, сирена, для себя, и я буду любить». 2 Этот намек здесь предполагает прелюбодейную фантазию, которая включает переключение привязанности с жены на любовницу; по крайней мере, так считает Люсиана. С древних времен русалок характеризовали как «непостоянных», «скользких», «опасных» и «очаровательных». 3 Они использовали свои отличительные голоса и соблазнительные музыкальные тексты, чтобы заманить в ловушку и поглотить несчастных моряков. Несколько лет спустя, в Сон в летнюю ночь (около 1595 г.), Шекспир снова включил намек на русалку, когда он пишет «Русалка на спине дельфина / Произносит такое приятное и гармоничное дыхание », что« некоторые звезды безумно выстреливали из сфер / Чтобы услышать музыку морской горничной ».

Ключевые слова

Ранний современный период Иконическое изображение Forman Armorial Иконический символ Facsimile Edition

Эти ключевые слова были добавлены машиной, а не авторами. Этот процесс является экспериментальным, и ключевые слова могут обновляться по мере улучшения алгоритма обучения.

Это предварительный просмотр содержимого подписки ,

войдите , чтобы проверить доступ.

Notes

1.

Petrarch,

The Essential Petrarch ed. and trans. Peter Hainsworth (Indianapolis and Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Co., 2010), 76.

Google Scholar2.

William Shakespeare,

The Comedy of Errors, from

the Complete Signet Classic Shakespeare, ed. Sylvan Barnet (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972), 3.2, lines 45, 47.

Google Scholar3.

Carol K. Mack and Dinah Mack’s

A Field Guide to Demons, Fairies, Fallen Angels, and Other Subversive Spirits (New York: Owl Book, 1998), 11.

Google Scholar4.

Антония Фрейзер приводит эту ссылку в

Мария Королева Шотландии (Нью-Йорк: Delta Book, 1969), 309,

Google Scholar5.

Рета М. Варнике, «Противостояние невзгодам, март 1566 г. - май 1567 г.» в

Мария Королева Шотландии (Лондон и Нью-Йорк: Рутледж, 2006), 146.

Google Scholar6.

«Заяц» в

Словарь символов пингвинов , изд. Жан Шевалье и Ален Гербрант и транс. Джон Бьюкенен-Браун (Нью-Йорк: Penguin Books, 1996),

Google Scholar7.

К. Х. Ферт, «Ballads and Broadsides», в

Шекспировская Англия: рассказ о жизни & amp; Поведение своего века под ред. Сидни Ли и К. Т. Луков, 2 тома. (Оксфорд: Clarendon Press, 1916), 2: 511–38.

Google Scholar10.

Джеймс Эмерсон Филлипс, Пролог,

Образы королевы: Мария Стюарт в литературе шестнадцатого века (Беркли: University of California Press, 1964), 6.

Google Scholar11.

Джон Маклауд,

Династия: Стюарты; 1560–1807 (Нью-Йорк: St. Martin’s Press, 1999), 83.

Google Scholar12.

John Guy, “Mary’s Story.” See esp. 361, in “

My Heart Is My Own”: The Life of Mary Queen of Scots (Hammersmith: Harper Perennial, 2004).

Google Scholar16.

Дженни Вормальд, «О браках и убийствах 1563–157», 166, в

Мэри, королева Шотландии: политика, страсть и утраченное королевство (Лондон и Нью-Йорк: Tauris Parke, мягкие обложки , 2001), 132–69..

Google ScholarВейр, «Укладывая ловушки для Ее Величества», особенно 362, 366, в

Мария, королева Шотландии и убийство лорда Дарнли (Нью-Йорк: издание в мягкой обложке Random House Trade, 2003) .

Google Scholar21.

Роберт Риддл Стодарт,

Scottish Arms: являясь коллекцией гербов: A.D. 1370–1678, факсимильное воспроизведение с современных рукописей с геральдическими и генеалогическими примечаниями (Эдинбург: Уильям Патерсон, 1881). Vol. 1. Интернет-архив. Библиотеки Университета Торонто. Доступно для онлайн-доступа по адресу

http://archive.org/details/scottisharmsbein02stoduoft. Accessed December 2009.

Google Scholar22.

Хью Кларк,

Введение в геральдику: с почти тысячей иллюстраций ред. Дж. Р. Планше, Somerset Herald of Arms, 18-е изд. (Тотава, Нью-Джерси: Tabard Press, 1974), 35.

Google Scholar24.

преподобного У. Одома, Мария Стюарт, королева Шотландии (Лондон, 1904 г.) (Чарльстон, Южная Каролина: BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2011 г.)

Google Scholar Андреа Альчати [

sic ]

Книга эмблем: Emblematum Liber

на латинском и английском языках < / em>, пер. и изд. Джон Ф. Моффитт (Джефферсон, Северная Каролина: McFarland & amp; Co., 2004 г.).Google Scholar27.

Дональд В. Стамп и Сьюзан М. Фелч, редакторы,

Елизавета I и ее возраст: авторитетные тексты, комментарии и критика Norton Critical Edition (Нью-Йорк и Лондон: WW Norton & amp ; Co., 2009 г.).

Google Scholar29.

“Heraldry,” in

The Book of Codes: Understanding the World of Hidden Messages; An Illustrated Guide to Signs, Symbols, Ciphers, and Secret Languages ed. Paul Linde (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2009), 228–29.

Google Scholar32.

Walter de Gray Birch, “The Renaissance—Mary Queen of Scots, and Her Successors,” 72, in

History of Scottish Seals Elibron Classics Series, vol. 1 (Stirling, 1905) (Charleston, SC: Adamant Media, 2010).

Google Scholar33.

Bruce A. McAndrew,

Scotland’s Historic Heraldry (Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 2006).

Google Scholar35.

Peter M. Daly, “How Many Printed Emblem Books Were There? And How Many Printed Emblems Does That Represent?” 216, in

IN NOCTE CONSILIUM:

Studies in Emblematics in Honor of Pedro F. Campa, ed. John T. Cull and Peter M. Daly. Saecvla Spiritalia: Herausgegbeben von Dieter Wuttke, vol. 46 (Baden-Baden: Valentin Koerner Verlag, 2011).

Google Scholar38.

Stephen Budiansky, in

Her Majesty’s Spymaster: Elizabeth I, Sir Francis Walsingham, and the Birth of Modern Espionage (New York: Plume Book, 2006),

Google Scholar39.

Mason Tung, “Emblematics,” in

The Spenser Encyclopedia ed. A. C. Hamilton, et al. (Toronto: Toronto University Press, 1990).

Google ScholarTung’s chapter on “Spenser’s ‘Emblematic’ Imagery: A Study of Emblematics,” in

Spenser Studies: A Renaissance Poetry Annual, ed. Patrick Cullen and Thomas P. Roche, Jr., vol. 5 (New York: AMS Press, 1985),185–207.

Google Scholar41.

Natale Conti,

Mythologiae chapter 24, “On Actaeon,” book VI, 564, in

Mythologiae trans. John Mulryan and Steven Brown, Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, vol. 316 (Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies Press, 2006), vol. 2.

Google Scholar50.

Andrew Zurcher, “Selections from the Poem,” 57n, stanzas 27–33, in

Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene:

A Reading Guide, Reading Guides to Long Poems (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011).

Google Scholar51.

Kerby Neill, “Spenser’s Acrasia and Mary Queen of Scots,” in

Publications of the Modern Language Association 60, no.3 (September 1945), 682–88.

CrossRefGoogle Scholar53.

Judith Yarnell, “Spenser, the Witch, and the Goddesses.” See esp. 139, in

Transformations of Circe: The History of an Enchantress (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1994).

Google Scholar56.

Although Francesco Colonna’s authorship has been disputed, I follow accepted practice by naming him as the author of

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili: The Strife of Love in a Dream (London, 1592) (Lexington: Theophania Publishing, 2012).

Google Scholar58.

A. Bartlett Giamati, “Inward Sound.” See esp. 95, in

Play of Double Senses: Spenser’s Faerie Queene (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1975).

Google Scholar60.

Godwin’s

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili: The Strife of Love in a Dream (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2005), 139.

Google Scholar61.

Edmund Spenser,

The Faerie Queene ed. A. C. Hamilton, et al., 2nd ed. (Harlow: Pearson Education Limited, 2007),

Google Scholar66.

Alastair Fowler, “The Emblem as Literary Genre,” 23, in

Deviceful Settings: The English Renaissance Emblem and its Contexts ed. Michael Bathand Daniel Russell, Selected Papers from the Third International Emblem Conference, Pittsburgh, 1993.

Google Scholar67.

Linda Shenk,

Learned Queen: The Image of Elizabeth I in Politics and Poetry (New York: Palgrave, 2010), 33.

Google Scholar68.

Michael Murrin, “Renaissance Allegory from Petrarch to Spenser.” See esp. 176, in

The Cambridge Companion to Allegory, ed. Rita Copeland and Peter T. Struck (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 162–76.

CrossRefGoogle Scholar71.

Donald V. Stump’s “The Two Deaths of Mary Stuart: Historical Allegory in Spenser’s Book of Justice,” in

Spenser Studies: A Renaissance Poetry Annual ed. Patrick Cullen and Thomas P. Roche, Jr., vol. 9 (New York: AMS Press, 1991), 81–105

Google ScholarKatherine Eggert finds difficulty with this interpretation, saying that it necessitates cutting off Mary’s head twice, 215n39, in

Showing Like a Queen: Female Authority and Literary Experiment in Spenser, Shakespeare, and Milton (Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press, 2000).

Google Scholar78.

Jeremy Tambling, “Medieval and Renaissance Personification,” 61, in

Allegory the New Critical Idiom (London and New York: Routledge, 2010), 40–61

Google ScholarJudith H. Anderson, “Androcentrism and Acrasia: Fantasies in the Bower of Bliss,” in

Reading the Allegorical Intertext: Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare, and Milton (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), 224–38;

CrossRefGoogle ScholarStephen Greenblatt,

Renaissance Self-Fashioning: From More to Shakespeare (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), 170–73;

Google ScholarHarry Berger, Jr., “Wring Out the Old: Squeezing the Text, 1951–2001,”

Spenser Studies: A Renaissance Poetry Annual, ed. Patrick Cullen and Thomas P. Roche, Jr., vol. 18 (New York: AMS Press, 2003) 81–121;

Google ScholarPatricia Parker, “Suspended Instruments: Lyric and Power in the Bower of Bliss,” in

Literary Fat Ladies: Rhetoric, Gender, Property (London and New York: Methuen and Company, 1987), 54–66.

Google Scholar80.

Edmund Spenser, “Muiopotmos,” 427, in

The Yale Edition of the Shorter Poems of Edmund Spenser ed. William A. Oram, et al. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1989), 406–30,

Google Scholar82.

“Arachne,” in H. David Bumble’s

Classical Myths and Legends in the Middle Ages and Renaissance: A Dictionary of Allegorical Meanings (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1998).

Google Scholar83.

Thomas P. Roche, Jr.,

The Faerie Queene, by Edmund Spenser (New York: Penguin Classics, 1987)

Google Scholar92.

A. D. S. Fowler examines the symbolic emblematic images of Temperance in “Emblems of Temperance in

The Faerie Queene, Book II,” see esp. 146,

Review of English Studies 11, no.42 (May, 1960), 143–49.

CrossRefGoogle Scholar

© Debra Barrett-Graves 2013

Авторы и аффилированные лица

There are no affiliations available

Personalised recommendations

Понравилась статья?

ПОДПИСАТЬСЯ на нашу рассылку новостей

и почему ему нравится принимать их форму., который открывается в том же окне (_blank в новом окне)

описание: ' варианты своего следующего фильма или драмы. .'

-

Стихи о вампирах

Эти проклятые этих отвратительных .

«На этих символических рисунках русалка представляет соблазн соблазнения и проституции?»

СИМВОЛА

ДУХ • ТЕНДЕНЦИИ ЗДОРОВЬЯ • ПОСЛЕДНИЕ • WELLNESS

Изображения предоставлены:

(Flames) Веб-страница о вампирских турах по Новой Англии.

Авторские права на все размещенные здесь работы принадлежат .

Как легко .

Условия

✳✳✳