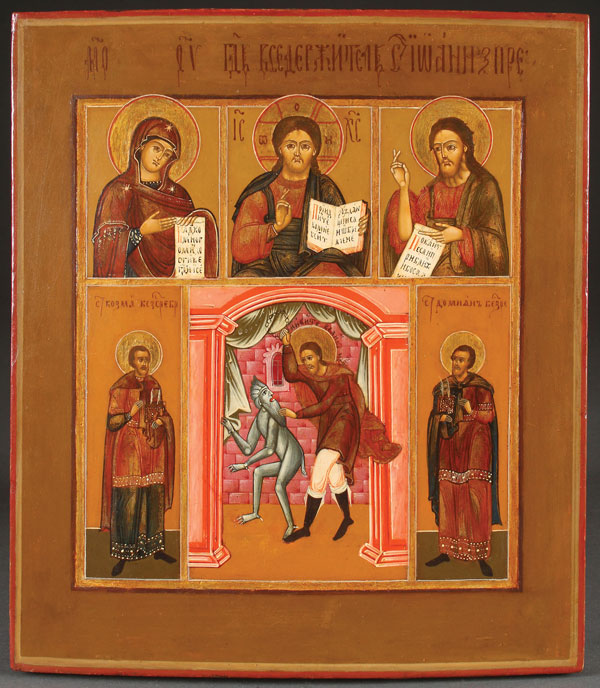

Today we will take another quick look at how to approach interpreting an icon. For that exercise, we will use this image:

The first step is of course to look at the whole icon, noticing what looks familiar and what does not. If you have been reading all the postings here, about two-thirds of this icon will already be familiar.

The second step is to look at and translate the inscriptions. That too should present no great difficulty if you have been reading this site.

Let’s begin with the top three images. You should already know that the image of Jesus in the center, with Mary at left and John the Forerunner (the “Baptist”) at right comprises a grouping known as the Deisis (from the Greek for “beseeching); the Russian term is just a variant of that, Deisus. The Deisis represents Jesus enthroned like an emperor in his heavenly court, with petitioners approaching at left and right to ask favors of him — in this case favors on behalf of humanity.

Now for the top inscriptions:

At left is the usual four-letter Greek abbreviation MP ΘΥ for Meter Theou, meaning “Mother of God,” the standard identifying inscription for Mary in both Russian and Greek icons. You will notice that it is right above the image of Mary.

Next is the inscription over Jesus. it reads ГДЬ ВСЕДЕРЖИТЕЛЬ. By now, you should recognize the first three letters as abbreviating the Church Slavic word GOSPOD’, meaning “Lord.” ВСЕДЕРЖИТЕЛЬ — VSEDERZHITEL’ — means “Almighty,” the equivalent of the Greek Pantokrator. So we can translate this as “The Lord Almighy,” which is the standard title for icons of Jesus seen as he is here, blessing with one hand and holding the Gospels in the other.

The inscription at upper right reads: СТ ИОАНН ПРЕ. CT abbreviates SVYATUIY, meaning “Holy/Saint.” IOANN is “John.” And ПРЕ abbreviates PREDTECHA, meaning someone who goes before, a “forerunner.” So this is “Holy John the Forerunner.”

At lower left is СТ КОЗМА БЕЗСРЕБР and at right СТ ДОМИАНЪ БЕЗРЕ. I mention them together because, if you have been reading recent postings, you will know they generally belong together. The inscription at left, in full, is Svyatuiy Kozma Bezsrebrenik, and that at right is Svyatuiy Domian Bezsrebrenik. Bezsrebrenik, I hope you recall, means “without silver,” usually translated loosely into English as “unmercenary.” So these two are the pair of physician saints Kosma and Domian, Cosmas and Damian.

That leaves only the lower central image, which is quite interesting. The letters above the saint’s head are quite small, but they read НИКИТА ВЕЛИКОМУЧЕНИК — Nikita Velikomuchenik. Usually the second word precedes the name, but in this icon it follows. Nikita is the saint’s given name, and Velikomuchenik means “Great (veliko-) Martyr (muchenik). So this is the Great Martyr Nikita.

The strange, greyish figure to his left has no halo, so we know he is not a saint. But what is he? Well, such figures with tail, long beard, and hair swept upward are the Russian way of depicting a devil. Often they are painted darker than here. And though it is rather difficult to see in this image, Nikita is holding a chain in his right hand as he grasps the devil’s beard with his left.

What does it mean? To know that, we have to know both the “official” story of Nikita (called Nicetas in the West) and the folk story.

It is said that Nikita was born into a wealthy family of the Gothic people who lived near the Danube River in the 4th century, in what is now Romania. He was baptized by Bishop Theophilus, said to have been a participant in the First Ecumenical Council. An intertribal war broke out, and Nikita became a soldier on the Christian side, that of the leader Fritigern. Their opponent was the leader Athanaric.

Fritigern’s forces defeated Athanaric, and Christianity was further spread among the Goths by Wulfila (Ulfilas), an Arian bishop who created a Gothic alphabet and translated the Bible into Gothic, an early Germanic language. Nikita also worked to spread Christianity and convert others to that belief. Given that both Wulfila and Fritigern were Arian Christians (not believing Jesus to be equal to God the Father) who did not accept the Nicene Creed, it appears that Nikita was also an Arian Christian, though of course that was downplayed when his cult was adopted into Eastern Orthodoxy. Some even think Nikita was ordained an Arian priest.

Over time, however, Athanaric regained power, massed forces and returned to attack and persecute the Christian Goths. Nikita was captured and tortured, and finally thrown into a fire (some say burnt at the stake in Moldavia in 378). In E. Orthodox tradition, he is said to have been martyred on September 15th in 372 (there is considerable difference in sources for dates in Nikita’s life and death). His relics were taken to Mopsuestia in Cilicia. After his cult of veneration spread, some of his relics were later sent to Constantinople, and some to Decani Monastery in Serbia, which still claims to have his “incorruptible” hand.

Now as to the tale of Nikita beating the devil, that is not part of the “canonical” story of Nikita. It is instead a product of the Byzantine Middle Ages that was adopted into Eastern Orthodox iconography. By this account, Nikita was actually the son of the Roman Emperor Maximilian. Persecuted by his father for holding the Christian faith, Nikita was severely tortured and cast into a prison for three years. While there, the Devil appeared to Nikita and tried to tempt him. But Nikita stepped on the Devil’s neck, and, broke his chains, and began beating the Devil with them. Then, called before the Emperor for questioning, he took the Devil with him to show the Emperor what he had been really worshiping. He also raised a couple of people from the dead, but Maximilian was still not convinced. Then his Queen and the people rose against the Emperor, and Nikita managed to baptize a huge number of people.

Because of this legend, in Slavic popular belief Nikita became Никита Бесогон — Nikita Besogon — “NIkita the Devil-beater,” and he became a very important saint because of his presumed power to drive away devils. Cast metal images of him, worn around the neck, were very popular.

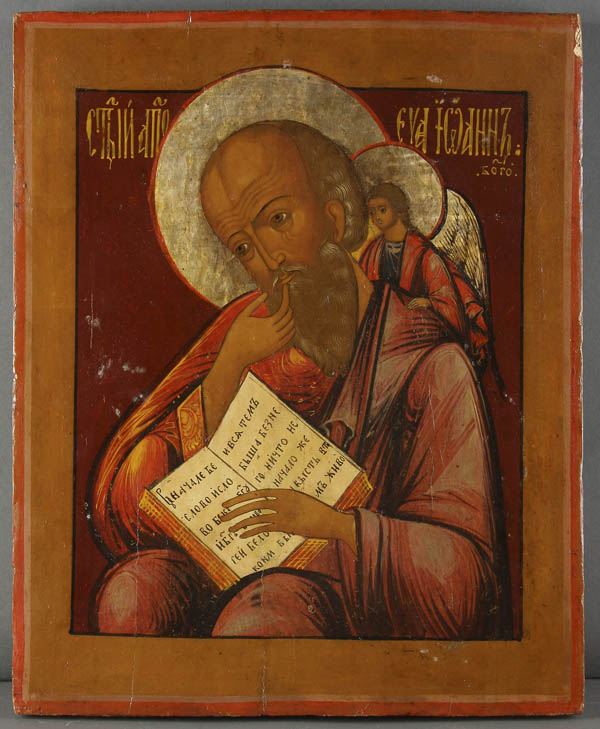

Here is another example of Nikita beating the Devil:

The title inscription reads:

АГ ВЕ МУ НIИКИТА

It abbreviates: ΑΓΙΟC ВЕЛИКОМУЧЕНИК НИКИТА

[H]AGIOS VELIKOMUCHENIK NIKITA

“Hagios” (Holy/Saint) is the Greek equivalent of the Slavic Svatuiy. One often finds it used in Russian icons. The remainder of the inscription is Church Slavic, and all together it reads:

“[THE] HOLY GREAT-MARTYR NIKITA”

Interestingly, the Patriarch Nikon, head of the Russian Orthodox Church in the mid-1600s, as part of his changes in the Church, declared that there was no “Devil-beater,” and that the name should not be connected with St. Nikita the Goth. However, the Old Believers saw this as just another deceit of the Devil, and they adopted the image of Nikita the Devil-beater as another sign of their “pure” faith, and so this type was preserved among the Old Believers right up to the present day.

Knowing that, let’s consider the icon pictured above again. We can see that not only is it painted in the stylized manner rather than the “Westernized” manner of the State Church, but the blessing hands of both Jesus and John the Forerunner show the fingers in the position used by and characteristic of the Old Believers, with the first finger straight up, the second finger slightly bent, and the thumb touching the bent last two fingers.

So, we see that:

1. The icon is in the stylized manner favored by Old Believers;

2. The icon uses the Old Believer finger position for the blessing hand;

3. The icon uses an iconography of Nikita preserved by the Old Believers as a sign of their “true belief” in contrast to the State Church.

All of those things tell us that is an icon painted by an Old Believer, not by a State Church painter.

Further, we should consider why the person ordering this icon would have asked for these particular figures to be painted on it. With the Deisis, the patron would have before him Jesus to receive his prayers; but also he would have the most important intercessors for humans, Mary and John the Baptist, to convince Jesus to answer his prayers. Then he would also have, to deal with any physical problems or illnesses, the two very important physician saints, Kozma and Domian (Damian). And finally, to keep away the powers of evil, he would have the most noted driver-away of devils, Nikita the Devil-beater. So to the Old Believer, this icon would have been a very good insurance policy for the difficulties of life.

Incidentally, you may sometimes see Nikita Besogon called Никита Чертогон — Nikita Chertogon (pronounced Chortogon); Chort is just the Russian term for “devil.” Both mean essentially the same thing — Nikita “Devil-beater.”

Here is an early 19th century Russian icon of Nikita”

We see the Nerukotvorrenuiy Obraz /”‘Not Made by Hands’ Image” of Jesus at the top, and the “family” saint Agripena/Agrippina in the left border.

url: '',

target: '_blank', // default is _self, which opens in the same window (_blank in new window)

описание: ' варианты своего следующего фильма или драмы. .'

url: '',

target: '_blank', // default is _self, which opens in the same window (_blank in new window)

описание: ' варианты своего следующего фильма или драмы. .'

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_telephone_box',

описание: 'The red telephone box is a familiar sight on the streets of the United Kingdom.'

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_telephone_box',

описание: 'The red telephone box is a familiar sight on the streets of the United Kingdom.'

описание: '',

описание: '',

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

url: 'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autumn',

описание: ' варианты.'

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',

описание: '',