— Ты это! А ты товой!

— Чего т-того?!

— Ты… это… не безобразничай.

— Ты это! А ты товой!

— Чего т-того?!

— Ты… это… не безобразничай.

Кино

Премьеры

Если мужчина сидел в тюрьме.

— А зачем нам?

— грабить!

Ричард Филлипс пережил самый длинный неправомерный тюремный приговор в американской истории путем написания поэзии и живописи акварелями. Но в холодный день в тюрьме он несли нож и подумал о мести.

Ричард Филлипс - это высокий человек с широкими плечами и привычкой петь к себе, обычно без слов, глубокого и радостного звука, который, кажется, поднимается из его души. он начал петь, когда он был мальчиком, и продолжал петь в тюрьме, и теперь поет в машине, а на обеденном столе, поддержав эту длинную ноту, как будто ничего в мире не мог остановить музыку.

Через два дня после того, как он был приговорен к жизни в тюрьме в 1972 году, Филлипс написал стихотворение. Возможно, это было первое стихотворение, которое он когда-либо писал. Ему было 26 лет, и покинул среднюю школу в десятом классе, и теперь, с большим количеством времени, чтобы удивляться, он сделал карандаш и поставил свое удивление на странице. Он задавался вопросом о цвете капли дождевых дождевов, цвет неба, цвет его сердца, цвет его слов, когда он пел вслух, и цвет его потребности в том, чтобы удержаться. Он пропустил, держа его дети, пропустил шнуровку своей обуви и вытирает слезы, и он знал единственный способ, которым он когда-либо вернулся к ним, чтобы как-то доказать свою невиновность.

Одно апелляция не удалась в 1974 году, еще одна в 1975 году. Филлипс думал, что он может победить с лучшим адвокатом, поэтому он сделал работу на лицензионной фабрике тюремной фабрики тюрьмы, в кафедре чернил, ловит свежеидал желоб и отправка их конвейерной лентой в сушильную печь. Заработная плата была плохами гражданскими стандартами, но хорош в тюремных стандартах, может быть, 100 долларов в месяц плюс бонусы, а Филлипс открыл банковский счет и смотрел, как деньги накапливаются.

Около четырех лет спустя ему было достаточно, чтобы заплатить один из лучших апелляционных юристов в Мичигане, поэтому он отправил в деньгах и ждал свободы. Все время он думал о своих детях, и вспомнил вкус домашнего мороженого, и писал любимых стихов для женщин, как реальных, так и воображаемых, с кроватями изготовленных из фиал и теплых ванн, сделанных из слез.

He waited, and waited. On January 1, 1979, a date confirmed by his journal, Phillips was in his room when another inmate walked in with some news. He’d just seen Fred Mitchell in the chow hall. It was a cold gray Monday at the Jackson prison, and Phillips had not seen his children in 2,677 days. Fred Mitchell? Phillips knew what to do.

On his way he stopped to tell a friend.

I’m coming with you, the friend said.

The prison was home to several factories. This meant easy access to raw materials, including scrap metal, which also meant an abundance of homemade knives. Phillips and his friend each held one under a sleeve as they stood outside the chow hall, waiting for Mitchell to emerge. Here he was, walking across the yard, unaware of the two men walking behind him.

Phillips could see it all in his mind. He would wait until Mitchell reached the Blind Spot, a well-known location the guards couldn’t see. He would plunge the shank into Mitchell’s neck. And he just might get away with it.

This would feel like justice.

Phillips was about 12 years old when his stepfather’s watch disappeared. It was a Friday night in Detroit around 1958. The stepfather had a thick leather belt. He took a drink of Johnnie Walker and asked Phillips if he’d taken the watch. Phillips said no. The stepfather beat him with the belt for a long time. Then he asked again: Did you steal my watch? Phillips said no. The beating continued. Did you steal my watch? No. The belt tore into the boy’s skin. His mother watched, too afraid to intervene. The stepfather asked once more for a confession. Phillips stood firm. The belt struck again, and again, and again, and finally it shattered some internal barrier. Did you steal my watch? Yes, the boy said, just to make it stop, and the young man who emerged from that beating told himself that was the last false confession he would ever make.

Some lies require more lies. Phillips had to account for the watch somehow, so he said he’d given it to another boy at school. The stepfather told him to go to school Monday and get it back. Phillips went up to sleep in the roach-infested attic, as he did every night, and wondered how to conjure a watch out of thin air. The next morning he ran away. He gathered a can of pork and beans and a can opener and a few slices of bread and an empty syrup bottle full of Kool-Aid and he crammed them into his lunchbox and walked outside into his new life. That night he slept on the hard floor of a vacant house, aware that he had no one in the world but himself.

The police caught him the next day. His stepfather beat him again. And alone in the attic or on the streets of Detroit, Phillips taught himself how to survive. How to steal cherries from other people’s trees. How to have a vicarious Christmas morning by talking his way into a neighbor’s house and watching other children open their presents. How to escape into his own mind by drawing pictures: an airplane, or Superman, or even the Mona Lisa, with a pencil on a piece of cardboard.

On those streets, he made the friend who would betray him.

Little is known about the life of Fred Mitchell beyond a few memories of old acquaintances and the occasional mention in official records. When this reporter approached his sister in late 2019 to ask about Mitchell, she said, “Get the f--- off my porch.” Anyway, he was a good baseball player in the old days, when a lot of boys looked up to the great centerfielder Willie Mays. Fred Mitchell could chase down a deep fly and catch it over his shoulder, just like the Say Hey Kid.

When they were not playing baseball, Phillips and Mitchell and their friends skipped school and played with BB guns and drank beer in alleys and fought in backyards and played hide-and-seek with the cops. They were juvenile delinquents on the verge of becoming hardened criminals in a city where violent crime was all around.

A single issue of the Detroit Daily Dispatch newspaper gives a sense of the chaos and desperation. A man told police, “I have shot four men today.” Two women fought with knives; one was stabbed to death. Kidnappers robbed and raped a doctor’s wife. It was December 13, 1967. At the bottom of Page 2 was a brief item about a 19-year-old man pleading guilty to manslaughter. This was Fred Mitchell, who quarreled with another young man and then shot him to death.

By this time, Phillips had taken a better path. After a joyriding conviction led to a brief prison sentence, he took a typing class and learned to type 72 words per minute. Out on parole, he turned this new skill into a good job at the Chrysler plant in Hamtramck, typing out time sheets and bills of lading for $4.10 an hour—more than $33 an hour in today’s dollars. He put on a suit in the morning and rode the bus to work, spending less time with the old crew.

Phillips had a strong jaw and an easy manner. He charmed the young ladies. One day a girlfriend named Theresa told him she was pregnant, and the baby was his. Phillips stayed with Theresa, and their daughter was born, and they got married and had a son. Theresa worked in a bank. They rented a modest apartment on Gladstone, and Phillips bought a Buick Electra 225. He gave his children the things he never had: abundant love, fancy new clothes, armloads of presents under the Christmas tree.

In 1971, the year Phillips turned 25, things began to unravel. He played around with some pranksters at work, and one prank went too far. Someone dropped a lit cigarette into a guy’s back pocket, and the guy said Phillips did it. Phillips denied it, but he lost his job anyway.

Around this time, Fred Mitchell got out of prison. Jobless and shiftless, with his marriage floundering, Phillips returned to his old friend. These days Mitchell ran with a big white guy he’d met in prison. They called him Dago. The three men went to shows at night and snorted heroin in motel rooms.

Phillips lived a double life, dangerous and unsustainable, a drug addict by night and a father by day. One day in September, he took the children to the Michigan State Fair. His daughter, Rita, was 4. His son, Richard Jr., was 2. They rode the Ferris wheel, crashed around in the bumper cars, and posed together for an instant photograph that was printed on a round metal button. That night Phillips went out and never came home.

Forty-six years later, legal observers would say Richard Phillips had served the longest known wrongful prison sentence in American history. The National Registry of Exonerations lists more than 2,500 people who were convicted of crimes and later found innocent, and Phillips served more time than anyone else on that list. Undoubtedly, the justice system failed him. The police failed. The prosecution failed. His defense attorney failed. The jury failed. The trial judge failed. The appellate judges failed. But on that cold day in the prison yard, as he walked toward the Blind Spot with the homemade knife under his sleeve, Richard Phillips was not thinking about a nameless, faceless system. He was thinking about the man who put him there: his old friend Fred Mitchell.

Here’s how it began: On September 6, 1971, two men walked into a convenience store outside Detroit. The black man stood watch near the door. The white man pulled a gun and demanded money. They drove off with less than $10 in stolen cash. An alert citizen noticed the car driving erratically and called the police. The registration came back to Richard Palombo, also known as Dago, who had stayed the previous night with Mitchell and Phillips at the Twenty Grand Motel in Detroit.

Palombo knew he was caught; he would plead guilty to armed robbery. But who was his accomplice? Phillips and Mitchell were both detained shortly after Palombo was. The two men looked similar. In a lineup at the station, two witnesses looked them over. They agreed that the second robber was Richard Phillips.

At Phillips’ trial in November, Palombo took the witness stand and told the jury how he committed the robbery. The prosecutor asked who else was there.

“I don’t want to mention the name,” Palombo said.

The judge ordered a recess. After the jury left, he asked Palombo, “Are you afraid of somebody?”

“No,” Palombo said, “I am not afraid of anybody.”

“Is your silence because you did not wish to incriminate someone else?” Phillips’ lawyer asked.

“Yes,” Palombo said.

His silence about the crimes of 1971 would stretch out for 39 years, with disastrous consequences. Even though one prosecution witness wavered between identifying the second robber as Fred Mitchell or Richard Phillips, the jury found Phillips guilty of armed robbery. He was sentenced to at least seven years in prison. And he was still in prison the next winter, when the body of Gregory Harris turned up.

Harris was a 21-year-old man who disappeared in June 1971 after going out to buy cigarettes. His wife found his green convertible the following night. There were bloodstains on the seats. Later that year, according to Detroit police documents, his mother told an officer about a strange phone call. She said an unknown woman told her, “I can’t hold it any longer, a Fred Mitchell and a guy named ‘Dago’ took your son out of a car at LaSalle Street. They shot him in the head and killed him. They then took him out near 10 Mile Road and tossed him from (the) car.”

It is not clear what the police did with that information.

On March 3, 1972, when a street repairman in Troy, Michigan, walked into a thicket to relieve himself, he saw daylight glaring off a shiny object. It was Harris’ skeleton, frozen into the ground. An autopsy showed the cause of death: multiple gunshot wounds to the head.

On March 15, Mitchell was arrested yet again — this time on more unrelated charges of armed robbery and carrying a concealed weapon. The next day, he told police he had information on the death of Gregory Harris. He said the killers were Richard Palombo and Richard Phillips.

The authorities had no physical evidence connecting their suspects to the crime. They had no circumstantial evidence, either. But with the sworn testimony of one man, the police could say they had solved a murder.

When Mitchell took the witness stand on October 2, 1972, to testify against Palombo and Phillips, Palombo’s attorney asked the judge to inform the witness of his right against self-incrimination.

“It’s my opinion that his testimony involves him in a serious crime,” the attorney told the judge.

By Mitchell’s own testimony, he knew about the murder plot before it was carried out. He played a role in the murder by calling Gregory Harris and luring him into a trap. He was arrested in possession of what may have been the murder weapon. And under cross-examination, he admitted to a possible motive: While Mitchell was in prison, Gregory Harris may have stolen a $500 check from Mitchell’s mother’s purse.

But for reasons that have never been revealed, and probably never will be, the state of Michigan put forth another theory of the case. Building on Mitchell’s testimony and little else, the prosecutor tried to persuade the jury that Mitchell had heard Palombo and Phillips conspiring to kill Harris, apparently because one of the Harris brothers had robbed a drug dealer, a purported cousin of Palombo.

Neither Mitchell nor the prosecutor ever tried to explain why Richard Phillips would have taken part in a revenge killing on behalf of the cousin of a man he barely knew. Later, Palombo’s father took the stand and said the cousin did not exist.

If investigators ever dusted Harris’ car for prints, they did not present that evidence at trial. Nor is there any record they analyzed the blood found in Harris’ car. Despite all this, Phillips’ court-appointed lawyer, Theodore Sallen, was curiously silent.

He did not give an opening statement. He let Palombo’s attorney do almost all the cross-examination. He never challenged Mitchell. He did not call one witness or introduce any evidence. He kept Phillips off the witness stand because he didn’t want Phillips to be questioned about his robbery conviction. When it came time to give a closing argument, Sallen said, “You know, they talk about Gregory Harris being dead. I don’t know if Gregory Harris is dead.”

The jurors deliberated for four hours before finding Palombo and Phillips guilty of conspiracy to murder and first-degree murder. Before handing down a sentence of life in prison, the judge asked Phillips if he had anything to say.

“Not necessarily, your honor,” Phillips said, “except for the fact that I was not guilty, you know, even though I was found guilty. And it’s not too much can be done about it right now to correct the injustice already, so all I can do is just, you know, wait until something develops in my favor.”

And so he waited, trying not to kill anyone and trying not to be killed. He knew one man so afraid of the rapists that he drank a jar of shoe glue and escaped them forever. He knew another so haunted by his own crimes that he jumped over a railing and plummeted to his death. Richard Phillips waited in his cell, subsisting on coffee and watered-down orange juice, reading Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations.

He saw children visiting other inmates, saw guards searching diapers for contraband, and he resolved to spare his children from that experience. He wrote his wife a letter, told her not to visit, not to bring the children, told her to move on and find someone else. Eventually she did.

On January 17, 1977, in a poem called “Without a Doubt,” he wrote these verses:

Ain’t it a crime

When you don’t have a dime

To buy back the freedom you’ve lost?

Ain’t it a sin

When your closest friend

Won’t lend you a helping hand?

Ain’t it a rule

That’s taught in school

That says “Be kind to your fellow man?”

Ain’t it odd

That when you pray to God

Your prayers don’t seem to be heard?

Ain’t it sad

When you’ve never had

The freedom of a soaring bird?

We all have a thousand possible lives, or a million, and our surroundings change us, for better and worse. Phillips always hated smoking, despised his stepfather’s Camels, trashed his own wife’s cigarettes whenever he could, and then he got to prison and reconsidered. Prison made him hyper-vigilant, always watching and listening, finely attuned to the danger all around. Sometimes he needed a cigarette just to calm his nerves. In prison, you didn’t throw away a half-smoked cigarette. You savored it, right down to the filter.

One December, a stranger handed Phillips two packs of cigarettes and said, “Merry Christmas.” After that, Phillips gave presents to other inmates: a book for one guy, a package of cookies for another. It felt good. Through a program called Angel Tree, he picked out toys and had them sent to his children. He didn’t know whether they’d been received. In 1989 at the Hiawatha prison on the Upper Peninsula, administrators held a contest for best Christmas song. Phillips won a $10 prize for a song with this chorus:

So just give me your love for Christmas

For love is all that I need

And if you give me your love at Christmas

My Christmas will be merry indeed.

There was another contest that year, for the cell block with the best snow and ice sculptures. In the prison yard, Phillips and his neighbors built a nativity scene and other decorations, including a seal balancing a ball on its nose. Then a guy from another block kicked the head off the lamb and smashed the ball off the seal’s nose. Phillips was furious. He stepped up to the guy, who weighed about 300 pounds, and said, “You’re disrespecting Jesus Christ.” Neither man backed down. A crowd gathered. Chaos ensued.

In this chaos, according to a guard, Phillips grabbed the guard’s shoulder and spun him around. Phillips denied it, and the report said he produced the names of 56 defense witnesses, but the prison investigator contacted only four of them. There is no surviving record of what they said. Nor is there any indication in the report that anyone corroborated the guard’s story. Nevertheless, authorities believed the guard. Phillips was found guilty of assault and battery on staff. He spent Christmas in solitary confinement, on a bed with no sheet, with food pushed through a slot in the door.

The next year he turned 44, and had a creative awakening. Phillips wrote at least 31 poems in 1990. He wrote about the vibration of crickets, about skylarks racing through the night. He recalled a sycamore tree in Alabama, from the early days when he lived with a kind aunt and uncle and an older cousin who carried him on her hip. He imagined himself dying, leaving on a train in the dark, serenaded by an orchestra and a blues band all at once, receiving a standing ovation. He burned with desire, imagining one woman in a rose-colored dress, and another so luminous that she singed his hair with her flickering light. He saw tulips opening in the garden, flocks of birds coming in from the south. He saw his own hair turning white.

“What I wouldn’t give — to be a young me — once again,” he wrote. “The clock hand spins like the water wheel on the side of an old shack. Everything has been for a reason. Nothing can be turned back; especially not time.”

This was his most prolific year as a poet. It was also the year he stopped writing poetry, because he found something he liked even more.

He’d been drawing with pencil occasionally since the mid-80s, after he finished his GED and associate’s degree in business, and in 1990 he decided to add some color. He sent away for an acrylic paint set, or at least thought he did. What came back was an Academy Watercolor Artists’ Sketchbox Set, an accident that changed the course of his life.

He opened the set. He took out the paints. And he began to experiment. Phillips had taught himself to draw, and to live, and now he taught himself to paint. He got it wrong at first, and then began to get it right: mixing the water and paint, keeping the brushes clean, letting the colors spread across the page.

He read art books from the prison library for technique and inspiration. He admired the work of Picasso, Da Vinci, and especially Vincent Van Gogh, another man who suffered, locked away in an institution, struggling to keep his sanity. Van Gogh and Phillips kept on painting.

The artist needs raw material for his work: the sunset, the garden, the lilies on the pond. Phillips did not have these, so he used pictures from books, newspapers, and magazines, combining them with his vivid imagination. And so, from inside the Ryan Road prison in Detroit, he painted a scene of three horses kicking up dirt on a racetrack. The better he got, the more he enjoyed it. Painting became an addiction. He woke up and couldn’t wait to get breakfast, drink his watery orange juice, and come back to his art. By then his roommate would be gone for the day, in the yard or at work, and Phillips could turn on his music. Outside inmates yelled, guards barked, dominoes fell, ping-pong balls smashed, showers hissed, toilets flushed, televisions blared, but Phillips put in his headphones and drowned it all out. All he could hear was John Coltrane or Miles Davis, focusing his energy, guiding his next brushstroke.

He painted a jazz trumpeter, a glass of wine with a cherry in it, a vase of yellow flowers on a table next to a picture of a tall ship on the high seas. He lost himself in the work so thoroughly that once in a while he forgot about his case, his endless appeals, his 20-year search for a judge who might believe him.

She knew men lied when they were caught. Even in her days as a defense attorney, Judge Helen E. Brown didn’t believe half her own clients. A guy would tell some cockamamie story, and she’d review the evidence, and then she’d go back and ask him what really happened. Now, in Wayne County Recorder’s Court, where she dispensed justice to killers and rapists and child abusers, she sensed that most of the defendants looking up at her were guilty of something, whether or not it was precisely the crime set forth in the indictment.

And then, in 1991 and 1992, she reviewed the appeals of two more men in a long parade of men who claimed to be innocent. When she read the trial transcript, Judge Brown was astonished. It seemed to her that Richard Palombo and Richard Phillips had been convicted of murder on the uncorroborated testimony of a single witness. If all cases were this flimsy, she thought, anyone could accuse anyone of anything and get them sent to prison.

Furthermore, she would say later, “All the evidence looked like it was against the witness.”

The judge was curious. She read the court file on Fred Mitchell’s robbery case from 1972, which was pending at the time of the murder trial, and found this quote from a trial judge: “Mr. Mitchell, when I read your record, I was going to give you life. Then as I read on, I realized what case this was, and I realized that you have been instrumental in helping on a first-degree murder case and that you deserve some consideration.”

It seemed that the more Mitchell cooperated, the lighter his sentence got. The judge reduced a potential life sentence to 10 to 20 years. Later, after Mitchell testified in the murder trial, his attorney re-worked the deal so he got only 4 to 10 years.

“In addition to all of the other obvious considerations,” Judge Helen Brown wrote after reviewing the file years later, “there must also have been a deal that Mitchell would never be charged with the murder, despite his having admitted under oath, on the stand, in open court that he was the person who set up the decedent to be killed.”

Brown concluded that the prosecution had made a deal with Mitchell and kept it secret from the defendants and the jury. In her view, “this constituted prosecutorial misconduct,” which meant neither Palombo nor Phillips received a fair trial. In 1991 and 1992, she ordered new trials for both men.

The Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office denied the allegation of misconduct and appealed her decision to the Michigan Court of Appeals, putting the men’s cases in the hands of three appellate judges. It is not clear whether these judges read the trial transcript. Two of them, Myron Wahls and Elizabeth Weaver, have since died. The third, Maura Corrigan, is now in private practice in Detroit. She declined to answer CNN’s questions. Regardless, the judges concluded there was not enough evidence to prove misconduct by the prosecutors. They reversed Brown’s order and reinstated Phillips’ conviction.

Phillips kept painting. He painted so much that the artwork piled up in his cell. This made it “excess property,” at risk of confiscation. Phillips made boxes from scraps of cardboard and mailed the paintings to a pen pal in upstate New York. Her name was Doreen Cromartie. She kept his paintings safe in the cellar, hoping he would pick them up someday.

In 1994, he painted a field of sunflowers against a lavender sky. He painted an old tree in the middle of the field. He painted low branches jutting off the trunk, just below the green leaves. And for a while he was not in prison. He was perched in the tree, breathing fresh air, looking out past the sunflowers toward the open horizon.

The boy was too young to understand why. He only knew that Daddy was gone, and now they were poor, living above a barbershop, paint chipping off the walls. Years passed, and his mother got a better job, a new husband, but Richard Phillips Jr. did not get a new dad. He kept that old metal button, with the picture of himself and his dad on that day at the State Fair in 1972, and sometimes, when he opened his drawer to get his wallet, he looked at the picture again. Who was that man looking up at him? A good dad, he thought, trying to remember, but no, he kept hearing otherwise. Your dad is a crook. Your dad’s a piece of trash. Your dad is a murderer.

After a while, he believed it.

On October 20, 2009, the Michigan Parole and Commutation Board granted Phillips a public hearing. If he said the right things, the governor might commute his life sentence, and he might go free.

“So what’s important to us at this point,” board member David Fountain told him, “is that when we talk, we hear the truth, whatever the truth is.”

“All right,” Phillips said.

He was 63 years old, and had spent 38 of those years in the custody of the Michigan Department of Corrections, and he realized by now that people generally did not want to hear the truth, whatever the truth was, because in 1972 a man had lied, and that lie had apparently been believed by the police and prosecutors, or at least by the jury, and that lie had acquired the sheen of truth, the weight of authority, the force of justice, the power of the state, and so to dispute that lie was to make oneself a liar in the eyes of those who controlled his fate. Tell the truth, whatever it is? He was a boy, standing before his stepfather, swearing he never took the watch, and down came the belt, tearing into his skin, and the sentence would be commuted if only he would confess—

“So your testimony today,” Assistant Attorney General Cori Barkman said, “is that you had absolutely nothing to do with—”

“Nothing in the world,” Phillips said.

“—Mr. Harris’ death?”

“Nothing,” Phillips said, and went back to his cell to wait for a commutation that never came.

Richard Palombo had a reason for his long silence. He’d gone on the witness stand in 1971 and refused to name his accomplice in the robbery, and the judge asked him if he was afraid of someone, and Palombo replied, “I am not afraid of anybody.” But this was not true. In a telephone interview with CNN in 2019, Palombo said he had been afraid, afraid of Fred Mitchell, afraid to talk about what they did together in 1971.

“I just kept my mouth shut under threat for my life and my family’s life,” he said. “He told me to keep quiet, so that’s what I did.”

As time passed and his health deteriorated, Palombo’s fear mixed with guilt. He closed his eyes and saw the face of the dead man, Gregory Harris, and worried that Harris was waiting for him on the other side. Palombo had nightmares. He prayed for forgiveness. All along, he kept filing appeals, and when something worked he wrote to Richard Phillips and encouraged him to try the same thing.

They were lost in the system together. One motion was filed in 1997 and not heard until 2008, when Judge Helen E. Brown granted new trials once again. But the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office fought them relentlessly, always winning in the Court of Appeals or elsewhere, and by 2010 Palombo was ready to try something new. He was no longer afraid of Fred Mitchell, because he’d heard Fred Mitchell was dead.

On August 24, 2010, Palombo had a public hearing before the Michigan Parole and Commutation Board. If he said the right things, the governor might commute his life sentence, and he might go free.

He did not say the right things.

“Mr. Palombo, you have been convicted of first-degree murder and you received a life sentence for it,” Assistant Attorney General Charles Schettler Jr. told him. “I want you to tell me the details of that crime going right from the beginning; you know, when it was first planned, the inception of the crime, everything.”

“All right,” Palombo said. In prior statements about his case, he’d gone along with Mitchell’s story — the official story — about the crime: that Harris was killed after he robbed a drug house operated by Palombo’s cousin. Now he told another story, one that had never before come to light.

In 1970, while serving time at the Michigan Reformatory, Palombo worked in the kitchen with Fred Mitchell. They became friends. One day Mitchell had a visitor, and when he saw Palombo again he said a couple of guys had gone to his mother’s house and stolen a $500 check out of her purse. Mitchell told Palombo he would get those guys when he got out of prison.

Mitchell got out first, and Palombo followed. They met up and began planning a robbery at a convenience store. Palombo had a pistol. They cased out the store. But Palombo didn’t like Mitchell’s plan. It was daylight, and they had no getaway car, so Palombo said he would take the bus home. At the bus stop, he heard Mitchell calling his name. Now they had a car. Gregory Harris was driving.

“Get in,” Mitchell said. “I got us a ride.”

Palombo got in the back seat, ready for the robbery. Harris stopped the car and went into a store to buy cigarettes. Mitchell asked Palombo for the gun, and Palombo handed it over. Mitchell put the gun in his waistband.

“That’s the guy,” Mitchell said — one of the men who stole the check from Mitchell’s mother. “I’m going to get him.”

Harris came back and started the car. Sitting in the front passenger’s seat, Mitchell told him to drive into an alley where they could get out and rob the store. Harris pulled into the alley. Mitchell pulled out the gun and shot Harris in the head.

Time seemed to slow down for Palombo. Mitchell fired again. The gun sounded distant as smoke curled in the air. Harris opened his door and slid out of the car. Mitchell followed him across the front seat, stood over him, and shot him again.

“Come on and help me get him in the car,” Mitchell said.

Palombo complied. They put the body on the rear floorboard. Mitchell drove to the suburbs, along 19 Mile Road, and pulled off in a secluded field. Mitchell and Palombo carried the body into the field. They left it there and drove away.

Thirty-nine years later, as Palombo told this story at his commutation hearing, the assistant attorney general noticed someone missing: the second man convicted of Harris’ murder.

“Tell me about Mr. Phillips,” Schettler said.

“I didn’t meet Mr. Phillips until July 4th, 1971,” Palombo said, “at a barbecue at Mr. Mitchell’s house, which was about eight days after the murder.”

“And Mr. Phillips was totally innocent?” Schettler said. “He wasn’t even there?”

“That’s correct,” Palombo said.

Palombo never made it out of prison. His entreaties to the parole board had no effect. When the pandemic arrived in the spring of 2020, he was among those who tested positive for Covid-19. He died April 19 at age 71, with an appeal pending in the Michigan Supreme Court. But before he died, he’d taken another step to help his old co-defendant go free.

What does it take to reverse a wrongful conviction? Even with Palombo’s new revelation about the murder, delivered in sworn testimony in 2010 before at least three high-ranking officials of the Michigan justice system, it took another seven years.

There is no indication in prison records that anyone from the parole board or attorney general’s office acted on the new information. In 2014, Palombo took matters into his own hands. He asked his attorney to notify the Michigan Innocence Clinic in Ann Arbor, where co-founder David Moran read the hearing transcript. Moran and his law students dug into the case. They persuaded a judge to grant Phillips a new trial. A fearless defense attorney named Gabi Silver agreed to represent him. During informal discussions, the prosecution floated an idea: Phillips could plead guilty and walk away with time served.

Phillips had a response for that:

“I’d rather die in prison than admit to something I didn’t do.”

On December 12, 2017, after hearing Phillips’ testimony and taking note of his good conduct in prison, Wayne County Circuit Judge Kevin Cox did something astonishing for a first-degree murder case. He granted Phillips a $5,000 personal bond. Phillips didn’t have to pay anything now, or ever, as long as wore an ankle monitor and showed up for his new trial. Meanwhile he could go free for the first time in 46 years, if they could find him a place to stay.

In a staff meeting at the Michigan Innocence Clinic, a new administrative assistant took her seat. Her colleagues were talking about a client who needed lodging. It was almost Christmas.

Julie Baumer knew how it felt to get out of prison and look for a home. In 2003, her drug-addicted sister gave birth to a baby boy, and Baumer volunteered to care for him. The boy got sick. She took him to a hospital, where doctors found bleeding in the brain and suspected shaken baby syndrome. Baumer was arrested, convicted of first-degree child abuse, and sent to prison. Later, with help from the Innocence Clinic, she found six expert witnesses who testified at her second trial that the baby actually had a stroke. A jury acquitted Baumer, but she still remembered that first Christmas out of prison, when she had nowhere to live but a homeless shelter, and she realized, as other women pulled their children away, People think I’m a monster.

Anyway, she was free now, trying to rebuild her life, and when she heard about Richard Phillips, she said, “Let me take him.”

Baumer lived with her 86-year-old father, Jules, in a 900-square-foot ranch house in Roseville, about 15 miles northeast of Detroit. There was little room to spare, but her father didn’t object, because he remembered what he’d learned from the Book of Matthew: When you welcome a stranger, you’re welcoming Jesus Christ. And so Julie Baumer cleared the personal items out of her bedroom, remade the bed, and set herself up on a pull-out couch in the basement. It was December 14, 2017, and her phone was ringing. Phillips was on his way.

He was 71 years old, hair almost as white as the snow on the ground, and she thought he looked as if he’d been through the wringer. But he felt wonderful. This was almost 50 Christmases rolled into one, and she was showing him to his room: a real bed, soft pillows, fresh pajamas, a light switch he could flip whenever he wanted. He could go to the bathroom and close the door.

Baumer remembered her first meal after prison, a mediocre slice of pizza on the way to the homeless shelter, and she wanted to give Phillips something better. She didn’t have much money, but she did have a friend who liked to gamble at the MotorCity Casino downtown. She called her friend and asked if he had any vouchers for the buffet. He did.

They went downtown. Phillips filled his plate with chicken wings and barbecue ribs and mashed potatoes. There were lots of desserts, too, but Phillips wanted one in particular. Baumer went to the dessert station and asked for a bowl with two scoops of vanilla ice cream. She brought it back and set it down. Phillips brought the spoon to his mouth.

“Oh,” he said, “I remember that taste.”

She took him to Meijer, the cavernous supermarket, and watched him admiring the deep shelves of orange juice. Fresh-squeezed, with pulp, without pulp, Tropicana, Minute Maid, never from concentrate. He must have spent an hour taking in the glory.

Baumer knew this feeling, too, the deprivation of prison, the gradual rewiring of your brain, the sensory jolt of reentry to the outside world. For her it was soap and lotion, this weird craving while she was locked away, and she got out and went to Meijer and spent a long time inhaling the scent of berry shampoo. People didn’t understand how hard it was going to prison, and how hard it was coming home.

Not to mention the second trial, if indeed the state intended to try Phillips again. He’d been fighting the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office for 46 years, and neither side had given up.

These cases were exhausting, as David Moran had found at the Innocence Clinic. He’d won a few of them, but Wayne County Prosecutor Kym Worthy was a formidable opponent. Again and again, Moran and his students would conclude that a convicted person was innocent. They would file a motion. And then, even when Moran had evidence he considered incontrovertible, Worthy and her prosecutors would argue from one appellate court to another to preserve the conviction. The innocence lawyers had a term for this practice. They called it fighting to the death.

Valerie Newman had fought Worthy to the death more than once. Newman had won about a dozen exonerations and a US Supreme Court case in her 25 years as a court-appointed appellate defense attorney. She represented Thomas and Raymond Highers, two brothers convicted of murder in 1987, and persuaded a judge to grant them a new trial after new witnesses came forward. Although Worthy decided not to retry them, and the state later awarded them $1.2 million each for wrongful imprisonment, and she said in 2020 that “dismissing the case was the right thing to do,” Worthy made it clear at the time she did not believe they were innocent. “Sadly,” she said in a news release when charges were dismissed in 2013, “in this case justice was not done.”

All that to say Valerie Newman was surprised when Kym Worthy offered her a job.

Following the lead of other big-city district attorneys, Worthy was assembling a team of lawyers who looked for wrongful convictions and set the innocent free. And she wanted to put Newman in charge.

Newman’s colleagues were skeptical. You’re going over to the dark side, they told her. But Newman saw an opportunity. Inside the prosecutor’s office, she wouldn’t have to fight anyone to the death. If she investigated a case and believed someone was innocent, all she’d have to do is tell her boss about it and get the case dismissed. On November 13, 2017, she started her new job as director of the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Conviction Integrity Unit. Her first assignment was the case of Richard Phillips.

Along with Patricia Little, a homicide detective assigned to the CIU, Newman dug in. When they interviewed Richard Palombo, he finally named his accomplice in the 1971 robbery that first sent Phillips to prison. No, it wasn’t Phillips. It was Fred Mitchell.

Newman wondered if this was the start of a pattern: Mitchell committing a crime, blaming it on Phillips, and getting away with it.

Nearly five decades had passed, and witnesses were scarce, but they tracked down the murder victim’s brother. He gave information that corresponded with Palombo’s story about Mitchell wanting revenge on the Harris brothers. Alex Harris said there was a hit on him in June 1971, and he fled the state. He also said Mitchell’s sister told him that Mitchell had been involved in Harris’ death.

Something else was bothering Newman: the timeline Mitchell gave on the witness stand. With coaching from the prosecutor, he said he’d heard Phillips and Palombo plotting the murder about a week before it happened. But Palombo said he’d been in prison until two days before the murder. Newman checked the prison records. Palombo was right. Furthermore, Phillips could not have conspired with Palombo in June 1971. They met for the first time at a barbecue on July 4.

The story Mitchell told at the trial could not have been true. And now, 45 years later, the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office would admit it.

On March 28, 2018, after Newman and the judge signed an order dismissing the case against Phillips, Kym Worthy held a news conference. This time there were no caveats, no lingering doubts. It was a complete exoneration.

“Justice is indeed being done today,” she said.

Nineteen months later, in the car on the way to see his friends, Richard Phillips is singing again. The song has no name, no words, but it is his personal anthem: a long, joyful note, resilient, unquenchable. It’s a bright afternoon in October 2019, the maple trees blazing with color. He gets out of the car. A dog runs out to greet him. He has several adoptive families now, several homes in which he is always welcome, including this one, the home of Roz Gould Keith and Richard Keith. He texted them the other night to say he loved them. Now he walks inside, and Mr. Keith gets him a glass of orange juice, and he sits back in an easy chair with Primrose the dog snuggled up to him, and he and the Keiths tell the story of the Richard Phillips Art Gallery.

He struggled for a while on the outside, unable to find a job, crashing with a guy he met in jail, overwhelmed by a world he barely recognized. Then he thought of the paintings. He called Doreen Cromartie, his old pen pal in New York. Yes, she still had them. Over the years people had told her to give them away, drop them off at the Salvation Army, but she always knew he’d get free somehow and take them back. There were about 400 paintings. A little boy walking on a sand dune. A bare-chested warrior gazing at an orange sky. A blue river in autumn, stairs leading to the water’s edge. All the places he could not go.

All the places he could go.

He bought a bus ticket for New York to see the paintings and the woman who kept them. She had a suitcase full of his letters. They had been corresponding for 35 years. She thought she was in love with him, wondered if perhaps they could be together now in Rochester, but he needed his freedom and his old home. He collected the paintings and shipped them back to Michigan.

Phillips had met the Keiths through an old friend of theirs, his lawyer Gabi Silver. They owned a marketing company. Another innocence advocate, Zieva Konvisser, helped them arrange an art show in Ferndale. The curator, Mark Burton, put about 50 paintings on display. Attendance was perhaps five times larger than usual: professors, politicians, even the judge who dismissed the case. Phillips kept saying, “I’ve never done this before,” and he didn’t know how much to charge, so they settled on $500, but he sold about 20 paintings that night, and word got around, news stories proliferating, and the Keiths helped him build a website, and pretty soon they were selling for $5,000. Now he could pay his bills, could send Doreen Cromartie a check to thank her for making it all possible. He got a used Ford Fusion and learned to drive again. He spun around on the ice, went into a ditch, got back on the highway and kept driving.

Phillips says good-bye to the Keiths. Back in Southfield, he stops at the supermarket. He whistles a tune and saunters through the aisles, taking care to select low-sodium bacon. Also Hostess Donettes, glazed, which he says are not for him but actually for the deer who live in the woods behind his apartment. Then comes the orange juice: Tropicana Pure Premium, homestyle, some pulp, a sturdy jug with a satisfying handle. At the register he pays in cash, pulling on the ends of a 20-dollar bill to make a pleasant snapping noise.

Back at the apartment, a modest walk-up with a security gate, his painting of sunflowers hangs in the dining room. That one is not for sale. Phillips enjoys being in demand — enjoys the speaking engagements, the calls and texts from well-wishers, the invitations to visit friends — but this leaves him with little time to actually paint. He has no way of knowing that in five months or so, with the arrival of the coronavirus pandemic, he will be forced back into solitude. And that in those long hours alone in his apartment, he will lose himself once again in the lonely joy of making art.

Now he turns on some jazz, heavy on the saxophone, and takes a slice of leftover pizza from the refrigerator. He pours some barbecue sauce on the pizza and takes a bite.

“And as soon as my phone gets charged up,” he says, “I’ll call my son and see where his head is at.”

The younger Richard Phillips is 50 years old. His mother saw the news about the exoneration and called Gabi Silver’s office. Father and son met at the zoo. It was awkward, because the older Phillips’ roommate was there too, and because they had last seen each other when the boy was 2 years old. Something irretrievable had been lost. The son had learned how to paint, and in high school he won an award for his portrait of the actress Lisa Bonet, and his father had not been there to encourage him. Phillips’ daughter had moved to France, and she did not want to see him, and when a reporter emailed her to ask why, she declined to talk about it. The Phillips family had been torn apart. No wrongful-imprisonment compensation would ever put it back together.

“Hey,” the father says on the phone, inviting his son to meet for dinner.

“No, no, you don’t have to — listen. No. No. You wear what you feel comfortable with.”

“Be you. Do you. That’s all I’m sayin’.”

“Probably take us about 45 minutes to get over there.”

Rush hour in metro Detroit, the afternoon a darkening gray, Phillips singing again, percussion of the turn signal. He is asked if he ever imagined an alternate life, without Fred Mitchell, or the murder, or 46 years in prison.

“That is so hard to even think of,” he says. “What my life would’ve been like.”

“It’s a very good possibility I could’ve been dead, coming up in Detroit.”

“This is the pattern of life that has led me to this point. Can’t complain, ‘cause I’m 73 years old, and 95 percent of all the guys I knew are dead. So.”

He lists the guys from the old crew. One died of AIDS, another overdosed on drugs, another had kidney failure, another got diabetes, foot amputated, leg amputated, dead, dead, dead. Fred Mitchell, too—

The prison yard, 1979. The cold knife under his sleeve. Mitchell walking toward the Blind Spot. A debt payable in blood. A life for a life. Phillips felt dead already. They would bury him in a pauper’s grave. But at least he’d get even first, feel the knife go in.

Then he heard something, or felt it, a message flickering in his mind: Don’t kill him. Because you still might have a chance to get out of here.

They said he was a murderer. If he killed Fred Mitchell, they would be right.

And so he let Mitchell go, and Mitchell drank himself to death at age 49, and Phillips stayed in his cell, painting his way to freedom. He looked old when he came out of prison, blinking in the cold sunlight, but he got new clothes and dyed his hair, and he began to look younger, as if he had turned back time. Now he rides on the highway in the late afternoon, singing that song again: always old, forever new, the sound of wisdom and innocence.

Главная »

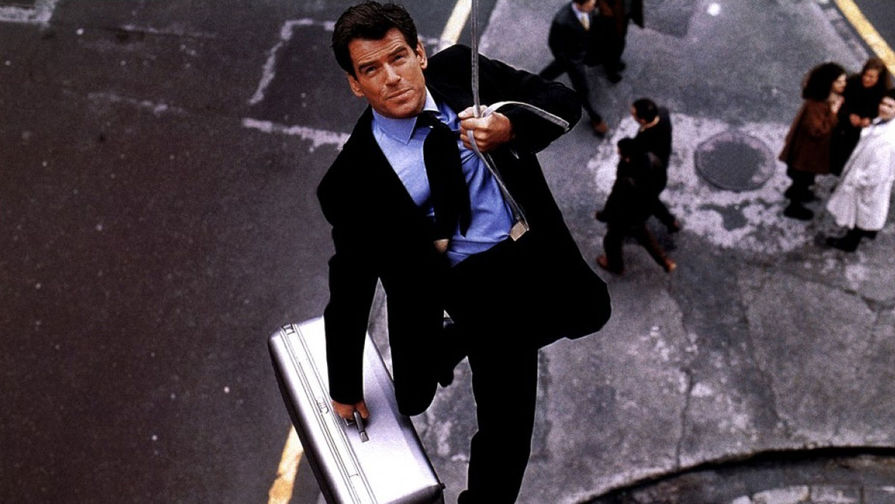

Человек ноября и роли Пирса Броснана против Джеймса Бонда

ФУНКЦИИ

(и Шон Коннери выходит на первое место).

проанализировал актеров Бонда, используя золотое сечение красоты Фи.

Главная »

Человек ноября и роли Пирса Броснана против Джеймса Бонда

ФУНКЦИИ

(и Шон Коннери выходит на первое место).

проанализировал актеров Бонда, используя золотое сечение красоты Фи.

ОПРЕДЕЛЕНИЕиз-за его «очень широкого лица»».

[5]. Текст взят из Википедии.